How active holdings punch below their weight for fund buyers; Finding Q2's big hitters

Welcome to Asset Allocator, FT Specialist's newsletter for wealth managers, fund selectors and DFMs. We know you're bombarded with information, so each day we'll be sifting through the mass to bring you what you need to know, backed up by exclusive data and research.

Forwarded this email? Sign up here.

At the core

Wealth firms aren’t exactly dogmatic when it comes to the active/passive debate, but they do have a clear preference. When it comes to conventional model portfolios, our analysis shows they overwhelmingly back active managers – at least in terms of the number of holdings used.

A shift in market conditions, or a further ramping up of cost pressure, could mean a change to this equation. But for now we’re testing another theory: whether core/satellite approaches mean passives have a bigger weighting in portfolios than the overall number of holdings suggest.

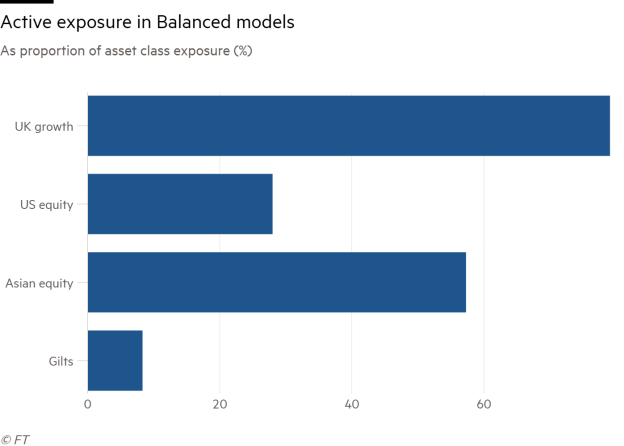

We’ve analysed a series of Balanced models to assess exactly how exposure is split across different asset classes. The findings for a selection of equity groupings – and for the gilts sector – are below.

The chart confirms that wealth firms do maintain hefty exposure to active names in some major areas – when it comes to UK growth allocations, many wealth firms still go 100 per cent active. But the other averages suggest a core/satellite leaning has a big influence on portfolios.

Take the US: while our previous analysis found DFMs used passives here more than anywhere else, they still only accounted for a third of holdings. But this data shows three-quarters of the typical wealth manager's US exposure is held in such products.

In Asia, too, while the number of passive holdings is relatively low, active funds only account for around 55 per cent of overall weightings. And in the bond space a previous finding holds true: most DFMs regard active gilt investing as a lost cause. We'll be taking a closer look at other sectors' dynamics over the coming weeks.

Square one

It was a quarter of much-needed good cheer, by and large: the biggest three-month rise for the FTSE All-World since 2012 (11 per cent), the best for commodities (up 15 per cent) in a decade, and healthy returns for most other risk assets.

The blemish in the global market make-up was that government bonds also had a good time of it. We've discussed the implications of those moves on several occasions in the past few weeks. But take a step back and it's unsurprising that every fund sector was up in Q1 - a sorely needed development following a 2018 in which no grouping made money, on average.

The stumble seen at the end of last year hasn't been erased entirely. In sterling terms, a handful of sectors remain well down on where they were at the end of September. Japanese equities and UK small-caps are still languishing 10 percentage points lower, while European funds are 6.5 per cent down.

Most other risk asset sectors are just about flat on a six-month view. Which brings us to the ever-present query for allocators: what happens next? The recession versus recovery debate has grown more urgent as bonds mimic equities' upwards rise.

This morning's data underlines how hard it remains to plot a course between fear and favour. Chinese manufacturing PMI numbers have got equities rallying, but they stand in stark contrast to data and sentiment surveys from elsewhere in Asia. UK manufacturing data has rebounded, too, but that was driven by stockpiling.

Among this haze, there is one rally that has yet to command the full attention of investors. Indian equities rose more than even Chinese stocks last month, rate cut expectations being a principal driver. If nothing else, that could provide fresh impetus for the EM rally in the coming weeks.

Man down

JPMorgan AM will be hoping lightning can strike twice following the departure of James Elliot from its multi-asset investment team. Mr Elliot's departure comes just over 12 months since Talib Sheikh left the business: both played leading roles on the Global Macro Opportunities fund that has become a fund selector favourite over the past five years.

Unusually, Mr Sheikh's exit didn't do much to derail that interest from fund buyers. Head of the multi-asset team he may have been, but the continued presence of Mr Elliot et al was enough to reassure holders. Global Macro Opps has continued to take in a sizeable amount of assets from UK investors over the past year - and performance held up well during the fourth quarter panic, too.

The question for buyers now is whether they still have confidence in the idea of a team-based approach, or whether losing two figureheads is a step too far.