The £1bn opportunity for fund buyers; Buy lists resist the lure of overseas stars

Welcome to Asset Allocator, FT Specialist's newsletter for wealth managers, fund selectors and DFMs. We know you're bombarded with information, so each day we'll be sifting through the mass to bring you what you need to know, backed up by exclusive data and research.

Forwarded this email? Sign up here.

Sizing up

Fund size isn't everything, but the consolidation of assets across the investment industry does have its consequences. A reluctance to back some lesser-known funds suggests DFMs are favouring established names with greater scale. Equally, however, wealth firms often tend to shun the very biggest products.

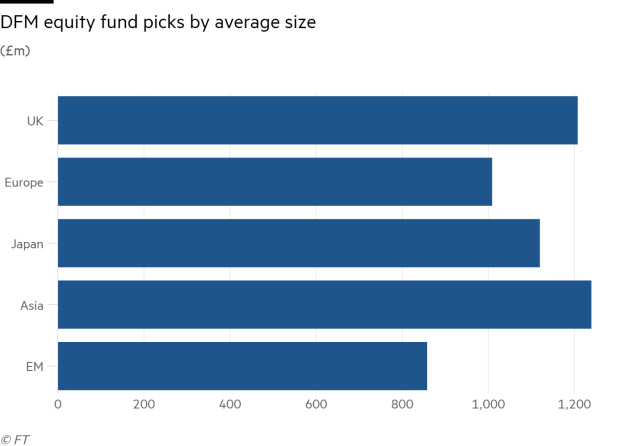

For a clearer view on the subject, we’ve broken down the size of the equity funds held by DFMs in our database. The average sizes for different regions are below:

Scale certainly remains a factor when it comes to bringing in the wealth crowd: even once the larger US market is excluded, the average equity fund held in every asset class bar EM has at least £1bn in assets.

The typical DFM fund pick is particularly large in both the UK and Asia, though this is partly a case of giants such as Lindsell Train UK Equity (£6.8bn) and Schroder Asian Total Return (£3.5bn) dragging up the averages.

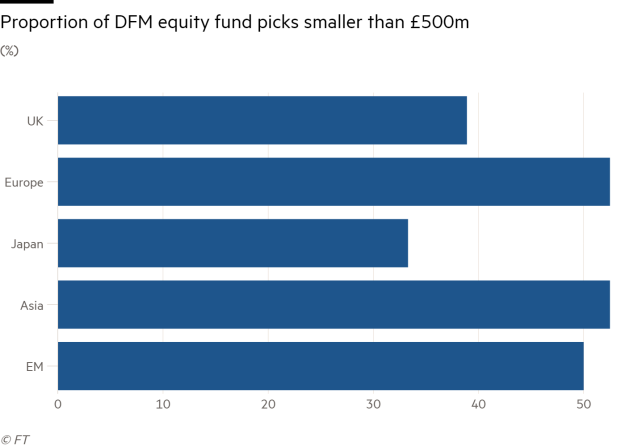

Indeed, a closer analysis shows that wealth firms are still backing plenty of funds lower down the scale. Below is a breakdown of how many sit under the £500m threshold.

It's no surprise that plenty of EM names are smaller, given the lower average fund size here. But the fact that more than half of Asian equity selections run less than £500m shows DFMs are using a wide range of different products - small and large. In the UK and Japan, however, the success of established names means there are few funds under the half a billion mark finding favour with discretionaries.

Strength in numbers

Monitoring individual funds’ returns (and size) is one thing, but nowadays wealth managers are also having to pay close attention to the performance of the parent companies. No active manager is an island: in an era of growing pressure on fund management firms, even the very best individual performers can head south - or just head for the exit - if the wider business is struggling to find favour with investors.

So Money Management’s annual Fund House of the Year survey, which ranks asset managers by the collective performance of their retail funds, is a good guide to those who are managing to insulate themselves from these stresses. This year Fidelity comes out on top, on both an absolute and a relative return basis.

There are a handful of firms whose ranges proved consistent performers both this year and last: no mean feat given the various changes in market conditions seen over that time. The likes of Janus Henderson, RLAM, Columbia Threadneedle and Baillie Gifford are among those who stood out in both 2017/18 and 2018/19.

Elsewhere it’s the individual asset class standouts that may provide food for thought for discretionaries. Cross-referencing these names with the most popular in our own database of DFM fund picks shows plenty of parallels: Axa IM was the best-performing fixed income manager in the last tax year, for instance, and DFMs in our database take a healthy interest in its funds, too.

By contrast, there are also plenty of victors that don’t tend to feature on fund selector buy lists - and many have one particular attribute in common. From Comgest to Capital Group to MFS Meridian, these are overseas asset managers trying to get a foothold in the UK market - and often failing to do so when it comes to attracting the attention of professional investors. DFMs may have reservations over issues such as manager access, and the question of how committed these firms are to the UK market. Alternatively, the results may indicate that discretionaries are simply too set in their ways.

Scaling new heights

One overseas manager that has long since established itself in the UK is Legg Mason. But the US firm’s decision to cut 12 per cent of its workforce has raised eyebrows here and abroad.

Lex describes Legg as a “minnow among whales” in the US, where its $750bn in assets pale in comparison to the likes of BlackRock and Vanguard. An alternative would be to consider it part of the squeezed middle, caught between boutique firms favoured by fund selectors and giants with the scale to stave off margin compression.

That begs the question of exactly how much scale is needed: Lex thinks the buffer required to ensure independence is no less than $1trn. The lack of UK firms above this size suggests that no domestic business is safe from the consolidation game.