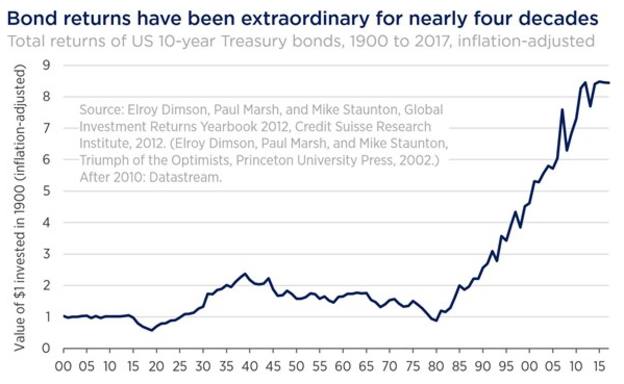

In addition, bonds have been an exceptionally rewarding asset class for nearly four decades.

The problem with this sort of thinking is that it overlooks the favourable tailwind experienced by bonds that stretches way back to the early 1980s.

As can be seen in the following chart, this exceptional period of performance has been quite unusual in the context of longer-term history.

In more recent times the tailwind has been reinforced by the unprecedented actions of central banks following the financial crisis.

To avoid a deflationary debt spiral, the Federal Reserve and other major central banks intentionally drove bond yields to historic lows and even into negative territory in some instances, sending bond prices soaring to new highs.

The return potential for many bonds now looks extremely limited. In addition to nosebleed prices and rock-bottom yields, the risks embedded in the bond market would appear to be well above average.

On the government side we observe taxes being cut, fiscal spending ramping up, and all at a time when government debt is already at or near all-time highs.

Governments and central banks are desperate to inflate away these debt burdens. Sustained negative real yields imply sustained negative real returns to holders of these nominal assets.

We also ask ourselves: “Who is the marginal buyer of bonds at these yields if central banks are stepping back?”

Historically it might have been large governments recycling their enormous current account surpluses.

If you export more than you import, you need to do something with the difference, and exporter countries have often been major buyers of importers’ bonds.

But the reduction of international trade imbalances is now top of the political agenda. In addition to political will, there are forces at work that should lead to a more natural reduction of the global gross trade surplus.

Examples include the seismic shifts occurring in China, where supply-side reforms have the potential to substantially boost imports, and in the US, where the shale oil and gas revolution is just beginning to impact the export picture.

The bond sell-off that spooked investors earlier this year in February — driven by greater-than-expected wage growth in the US — could be a harbinger of more volatility to come.

Negative returns are likely if interest rates continue to rise as quantitative easing begins to unwind. When yields are low, bond prices become extra sensitive to any change in yield (something called convexity), adding a whole other layer of risk.

Worse yet, there are signs that stocks and bonds are now moving together, thus negating the diversification benefit that one might expect bonds to provide.

Taking a longer-term view of history, the following chart shows that the strong anti-correlation between US stocks and bonds that we have seen since the late 1990s is something of an aberration.

Over recent decades, bonds have performed extremely well while also providing reliable diversification for stocks.

Expecting a repeat performance in the decades to come reminds us of the late financial historian Peter L Bernstein’s comment: “There is a difference between an optimist and a believer in the tooth fairy.”

Relying solely on bonds to manage risk at today’s prices strikes us as imprudent, at best.

Graeme Forster is an analyst at Orbis Investments