Article 4 / 5

The Guide: Outlook for 2017Conflicting trends will buffet sector

Emerging markets got off to a good start in 2016. However, the shine was taken off by Donald Trump’s victory in the US election.

Investors worried the emerging world would be hit by changes to US trade policy, as well as a stronger dollar resulting from a strengthening US economy.

Brazil, Turkey, Indonesia and South Africa are among the countries most exposed to a strong dollar and higher borrowing costs, while the potential for the introduction of import tariffs hit sentiment towards equities in Mexico hardest. Exports account for 35 per cent of Mexico’s GDP, and 80 per cent of its exports are to the US.

The possibility of a trade war with China, Mexico or others is a significant risk over the medium term. If it becomes clear Mr Trump does intend to pursue a hard line on trade, then it is hard to see anything other than a renewed sell-off.

Global trade growth has been an important driver of emerging market performance, and although there has yet to be any explicit mention of protectionist policies from Mr Trump, they were an important part of his campaign. Fortunately for exporters to the US, renegotiation is more likely than outright rejection of existing trade agreements.

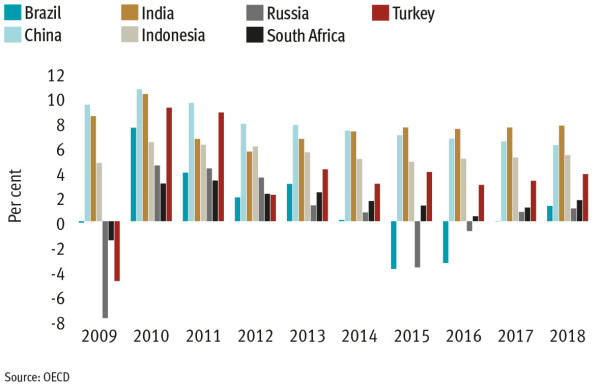

Although the political backdrop is uncertain, there are reasons for optimism on other fronts. Domestic growth in emerging markets continues to be strong; India and Indonesia stand out with predicted rates of around 8 per cent and 5 per cent for 2017, respectively.

This robust growth combined with declining capital expenditure and labour costs is positive, while a recovery in commodity markets is helpful for resources-orientated economies. Business confidence is improving in Brazil, which should exit recession in the coming year, while India’s renewed pro-growth focus should boost the economy.

Russia, a recent bright spot, is benefiting from a stabilisation in the oil price and expectations that tension between Moscow and Washington will ease under the new US administration. However, recent outperformance, particularly among small and mid-caps, is reason for caution.

China is likely to be the key economy to keep an eye on – recent growth has proved doubters wrong but has been at the price of worrying levels of indebtedness. This might not be a story for 2017 – the economy could surprise on the upside – but the build-up of debt combined with an ageing population will have consequences.

In the meantime, investors may choose to focus on relative value. Baidu is around half as expensive as Google on a price-to-earnings basis, for instance, and China’s large domestic consumer base looks in good health for the time being.

Thus, emerging markets look likely to be buffeted by a variety of potentially conflicting trends. On the one hand, uncertainty over US trade policy could dampen investor appetite further, with any greater dollar strength resulting from rising US interest rates overriding any positive factors due to rising debt costs.

However, emerging markets could likely withstand gradual tightening of Fed monetary policy (whereby the dollar doesn’t strengthen much further), with relatively low valuations, decent domestic growth and higher commodity prices providing support. Meanwhile, at a company level, although improved capital discipline and productivity are necessary to improve earnings growth and win over unconvinced investors, weak corporate profitability is, at least, easing.

Divergence within the asset class also looks highly likely, with geographic and sectoral winners and losers dictated by the permutations of possible US monetary, trade and fiscal policy, alongside local factors.

A particularly rosy scenario would see a widespread beneficial impact for emerging markets (especially exporters) if US spending results in a boost to global as well as US growth, US interest rates increase only marginally, and protectionist policies fail to materialise.

Perhaps most encouragingly of all, there is a healthy degree of scepticism and investors are generally light in the asset class, which often bodes well for future returns. Without rebalancing, a 10 per cent weighting in emerging markets within a typical global equity portfolio five years ago would be closer to around 5 per cent now; so there is scope for positive flows from investors moving into growth assets and out of defensives.

If there is an environment of higher growth and inflation, and the Trump effect on global trade turns out to be neutral or positive, then investors are likely to instinctively turn to the asset class.

Rob Morgan is pensions and investments analyst at Charles Stanley Direct