A “disorderly” exit by the UK from the European Union (EU) could see interest rates fall rather than rise, according to Bank of England governor Mark Carney.

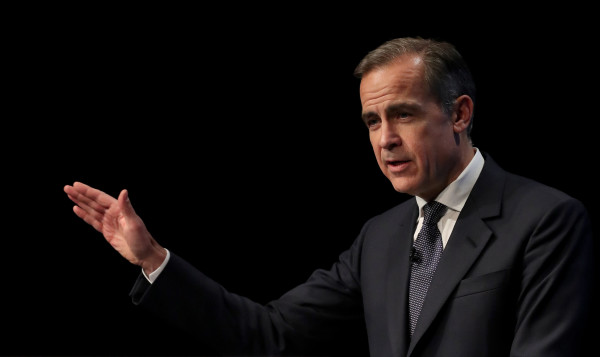

In a speech to the Society of Professional Economists in London on 24 May, Mr Carney said it remains the central bank’s base case that a deal on the terms of the UK leaving the EU will happen and interest rates will rise, if that is not the outcome then the Bank of England will have to change the course of its interest rate policy.

He said that while financial markets have repriced assets at least partly in expectation of a “disorderly” Brexit, consumers and households have not done this.

Mr Carney said the return of real wage growth, that is wages rising faster than inflation, would imply that consumer spending will rise.

But he said if consumers become as concerned about the outcome of the Brexit negotiations as households are, and decide to save the extra cash, or use it to reduce debt, then that would remove enough demand from the economy to drive inflation sharply downwards, below the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target.

He said this would justify the Bank of England to “respond” to the changing circumstances by either cutting rates or leaving them unchanged.

If economic conditions are such that the Bank of England is contemplating cutting rates, then it is likely sterling will have dropped in value against other currencies, and a rate cut would entrench this fall.

For equity markets a fall in sterling would enhance the value of the overseas earnings achieved by some companies, while denting the investment case for banks, and other businesses that earn the bulk of their income from within the UK.

If rates are being cut, then the likelihood is inflation is falling, and that helps the bond market, as the value of the fixed income from bonds is worth more.

He said if progress happened in the Brexit negotiations, then it might mean the business response to Brexit moves into line with that of the consumer, and the economy grows at a faster rate than expected, and rates rise more quickly than expected.

Mr Carney repeated his claim that UK households are on average £900 worse off than they would have been if Brexit had not happened.

This £900 is based on forecasts for future levels of growth made by central bank in May 2016, prior to the vote happening, those forecasts could have been inaccurate in either direction, whether the vote had happened or not.

He said Brexit has reduced the long-term equilibrium rate of growth in the UK economy by 40 per cent annually, to 1.5 per cent. This means he normal level of growth in the economy would be 1.5 per cent, with any deviation above or below that being the result of government or central bank policy that is nescessarily short-term in nature.

Jeremy Lawson, chief economist at Aberdeen Standard Investments, said a “no-deal” Brexit would likely mean that rates fall, and that any Brexit outcome which increases barriers to trade would reduce GDP growth for for both countries where the trade barrier applies.

David.Thorpe@ft.com