Article 1 / 4

Guide to investing in frontier marketsWhat are frontier markets?

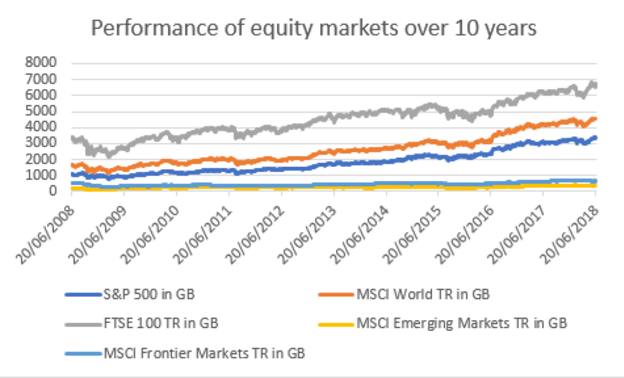

A UK investor who built up exposure to the MSCI Frontier Markets index a decade ago would have seen the benchmark gain just 18.7 per cent, paling in comparison with the S&P 500’s 211.2 per cent rise (see chart 1).

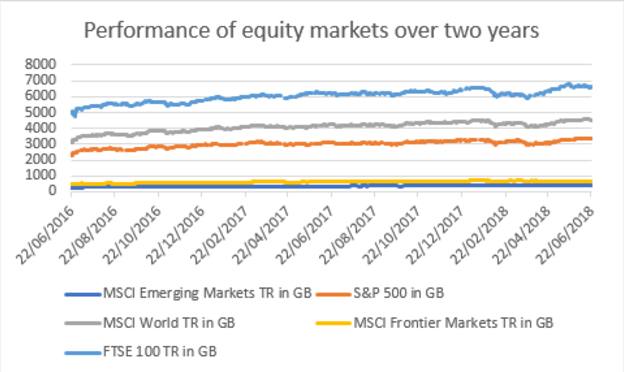

However, frontier markets have performed somewhat better more recently, returning 37 per cent in sterling terms over two years, outpacing the FTSE 100 and trailing other peers less severely (see figure 2).

Figure 1

Source: FE Analytics

Perhaps more significantly, commentators believe prices on “quality” assets – particularly bonds and equities in developed economies – look bloated after several years of strong performance. This leaves them exposed to a market downturn, but also has the potential to limit future returns.

Figure 2

Source: FE Analytics

On the other side of the coin, assets perceived as carrying greater risk have been tipped to lead the pack in the coming years.

Luca Paolini, chief strategist for Pictet Asset Management, has warned investors to “learn to love risk”, at least within an element of their portfolios, because this is where future returns lie.

“The default portfolio split evenly between the developed market stocks and bonds will no longer be able to deliver real returns most investors need,” he notes.

“Our economic forecasts justify an investment tilt to the emerging world.”

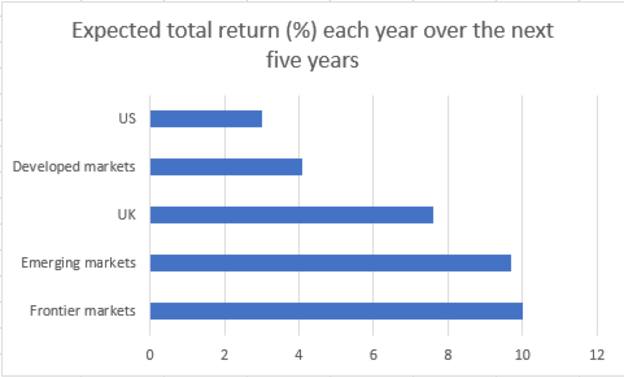

In a set of forecasts published in May, Mr Paolini predicted that frontier markets would deliver the best performance, returning 10 per cent each year for the next five years (see figure 3), with only emerging market Asia equities set to fare as well.

Figure 3

Source: Pictet Asset Management

Stocks in developed markets are expected to return just 4.1 per cent a year over the same period.

Frontiers vs emerging markets

So this is a set of countries worth considering. But it is also worth first explaining to clients what exactly frontier markets are, and how they differ from the better known emerging markets asset group.

Broadly speaking, economies are classed as developed, emerging or frontier markets based on how advanced and investor-friendly they are.

MSCI, the index provider, looks for “sustainability of economic development” when assessing prospective members of the developed group.

Evidence of this is not required for emerging or frontier market classifications, but emerging markets tend to be more accessible than their frontier counterparts.

By MSCI’s standards, emerging markets must have “significant” openness to foreign ownership, and meet the same level of quality when it comes to the ease of moving capital in or out of a country.

The requirements are less stringent for those classed as frontier markets: these countries must show “at least some” openness to foreign ownership and enable “at least partial” ease of capital flows. Frontier markets must show improvements in these areas to be promoted into the emerging grouping.

It is important to note that not all investors rigidly follow definitions set by index providers such as MSCI. But these do serve as a useful rough guide.

Geographical considerations may prove important for clients who want a stake in the success of particular regions.

Countries from Eastern Europe and Africa are prominent in MSCI’s Frontier Markets grouping. This includes the likes of Croatia, Kazakhstan, Serbia, Kenya, Morocco and Tunisia. This cohort also includes some names from Asia and the Middle East, including Vietnam and Kuwait.

The Emerging Markets list, by contrast, has a handful of members from the Americas, including Brazil and Mexico, and many more Asian countries. Among these is China, as well as Pakistan and Taiwan.

On the investment front, specialists have been quick to point out the limitations of the frontier markets grouping, including greater difficulty buying or selling holdings.

“Liquidity can be very poor in frontier markets so the tradability of securities is an important consideration,” explains Gill Hutchison, research director for fund ratings provider The Adviser Centre.

“The costs of accessing these markets is higher than they are for developed markets: trading, administration and custody costs are more onerous in less developed and more illiquid markets.”

Too high risk?

For some, these drawbacks are too great to overcome.

Rory McPherson, head of investment strategy at discretionary fund manager Psigma, explains: “They are pretty illiquid so it doesn’t really fit our ethos."

Scott Gallacher, an adviser, adds that such exposure would only suit certain clients.

“I’d suggest that this area is only appropriate for those with a higher risk approach to investment or as a very small part of a well-diversified portfolio,” he says.

But frontier markets could boost returns and add diversification to a portfolio, as they are not highly correlated to emerging or developed markets.

david.baxter@ft.com