Inherent bias

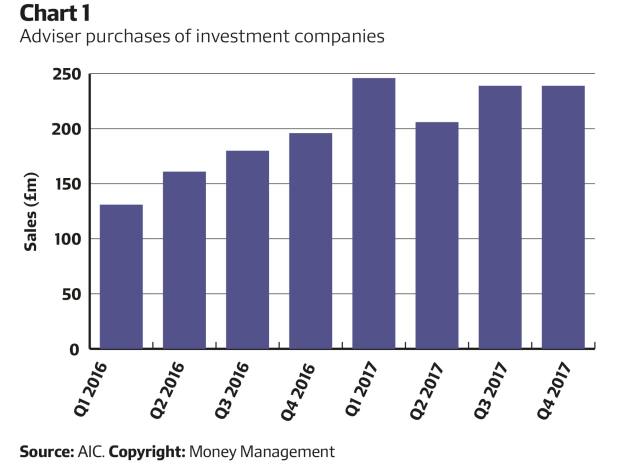

Chart 1 shows how interest has gradually increased since 2016. But a new report by specialist consultancy the Lang Cat identifies an “inherent market bias against investment companies” that takes many forms, such as the march towards vertical integration, the influence of networks, and the outsourcing of investment decisions to discretionary fund managers (DFMs) that don’t use investment companies in their model portfolios.

The Lang Cat’s analysis of the cost structures of adviser platforms reveals another considerable barrier to the wider uptake of investment companies.

The majority of platforms “remain hooked on the drug of unlimited percentage-based charging”, the report says, in contrast to many direct-to-consumer platforms where custody charges are capped or eliminated for investment company investors. That “unlimited percentage-based charging” is what makes unit trusts so unsatisfactory as an investment.

When it comes to the model portfolios used by DFMs and an increasing number of advisers to segment their client bases, the report finds there are many platforms where the cost of incorporating anything other than open-ended funds is “prohibitive”.

Watching costs

Stockmarket returns have never been generous compared with buying and selling goods, or creating businesses. They are small, and require years if they are to compound into fortunes. Thus investment costs have always been important to results, and are ignored by investors and advisers alike at their peril.

The Association of Investment Companies (AIC) is doing its best to persuade the FCA that competition between different styles of asset management, and different structures, are as important as analysis of annual results. But financial advisers might do better to remember Occam’s razor. This idea, attributed to a 14th century scholar, is the rule of thumb that suggests the simpler solution tends to be the right one.

The current investment philosophy embraced by the FCA goes back to the computer and the 1940s; that of the traditional investment company stretches back through hundreds of years of history.

There have always been people with cash, needing an income, and entrepreneurs with ideas wanting cash. First merchants, and then bankers, were the intermediaries. The successful were those that ensured the former did not lose their capital, because the latter knew what they were doing.

Such a service deserved a fee, which is why merchants and bankers became the richest people within their societies. Today, the world is far richer than it ever was, and more people have more money than ever before, but the need for safe income remains, as does the need for honest and intelligent advisers.

As Brexit negotiations enter their last few months, all sorts of fears are developing, from food and medicine shortages to a collapse of air transport. Whether talks are successful or not, no one can foresee, let alone predict, the outcome for the British economy, or the behaviour of sterling and the trend of the London stockmarket.

But even today, five years after RDR, some 95 per cent of investment assets are with open-ended funds. This means that, among all the uncertainty, the opportunity is huge for those who plump for the alternative.

In the words of the AIC, investment companies can provide better long-term performance, with the average investment company returning 165 per cent over the past 10 years, compared with 108 per cent for the average open-ended fund.

The need for income

What is certain is that those with money will need income from it, and preferably a rising income. This is particularly the case if the pound stumbles in the event of a poor outcome to Brexit, since a weak currency will certainly lead to inflation, as imported food and other necessities drive up shop prices.

As a result, intermediaries should consider not only investment trusts, but especially those designated by the AIC as dividend heroes – those that have succeeded in increasing their dividends every year for each of the past 20 to 50 years.

For safety, these should only be those with global mandates. We must hope that the UK will prosper outside of the EU, but we will not know if this is the case until the process is over.

Learning from the past

English schoolchildren are no longer taught about the South Sea Bubble of 1720. This was Europe’s greatest-ever banking crisis, involving London, Paris and Amsterdam: the central banking equivalent then of today’s New York. For the next 50 years, it was impossible to raise equity for business, but business needs did not go away because of the bubble.

Equity is the risk capital needed between the conception of a business and its conversion into a profitable and income-paying reality.

Without the possibility of issuing equity, Dutch merchants and London bankers had to collaborate in financing West Indian tobacco and sugar plantations, developing rum distilleries, as well as purchasing land and building houses in the US.

The solution was to amalgamate individual projects into one, but at different stages of development and income production. The land itself was also combined and collateralised on behalf of investors, so that what were equity investments could be dressed up as secure bond investments.

A century later, F&C used this technique to offer investors twice the yield available on British government bonds by investing in issues of colonial governments instead. The initial promise to investors was 6 per cent, but the average yield over the next 150 years was more than 8 per cent a year.

That result was not luck, but judgement. That is what investors need now, with the world yet to recover from the 2008 banking crash, and Britain lurching into the economic unknown.