But in recent months, the Trump administration’s protectionist agenda has become more apparent.

At first we saw tariffs on steel, aluminium, lumber, solar and washing machines based on tenuous national security grounds and other obscure trade laws.

The higher imported costs have probably done more damage to the users of these goods than the value of the jobs ‘saved’ in the protected industries, but the overall macroeconomic impact was negligible.

Then over the summer and in response to the investigation into China’s alleged theft of US intellectual property, the US imposed 25 per cent tariffs on $50bn (£38.5bn) of Chinese imports. This list mostly avoided consumer goods.

China retaliated proportionately, leading to Mr Trump firing the latest shot in his trade war: 10 per cent taxes on $200bn (£154bn) worth of Chinese imports. Furthermore, from January 1 2019, this figure could rise to 25 per cent — a delay intended to give US companies time to establish new supply chains.

In reaction, China’s response has been relatively measured, with variable tariff rates up to 10 per cent on $60bn (£46bn) of imports. True to form, Mr Trump has once again threatened to respond to any Chinese retaliation, with restrictions on a further $267bn (£205bn) of additional goods, covering nearly all of China’s imports to the US. This would raise prices on high-profile consumer goods such as TVs and mobile phones.

The tariffs so far will probably only make a minor dent in US GDP growth. But the danger of further escalation in trade tensions appears to be increasing.

For investors, the biggest uncertainty is the indirect effect: financial conditions and business sentiment could be shaken by changes to the global trade order.

Interestingly, the market reaction so far has been relatively muted. This may be because what began as a multilateral melee, with the US facing off against Mexico, Europe, Canada and China, has become a bilateral bust-up between Washington and Beijing. Market participants, moreover, may expect the recent US fiscal stimulus and Chinese currency weakness to mitigate any short-term negative impact of the fracas on the world’s two largest economies.

Yet this does not mean we can be at all certain as to how the situation might unfold.

Can Trump win a trade war?

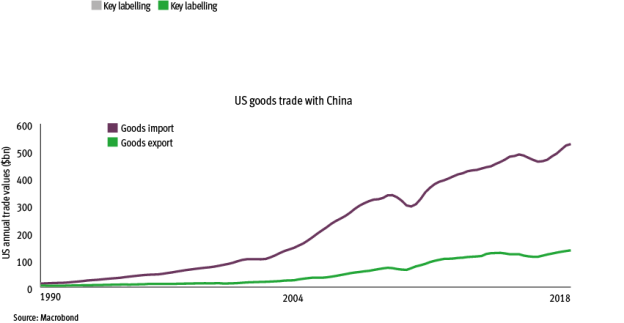

China cannot match Mr Trump’s tariff threat dollar for dollar as it only imports less than $150bn (£115bn) of US goods (see chart). However, the trade deficit vanishes when one considers US subsidiaries’ sales in China.

Source: Macrobond

China can retaliate by putting pressure on US companies operating in China. Customs delays, tax audits and increased regulatory scrutiny are possible, with Hollywood and US pharmaceutical companies easy targets.

China has also proven very effective in the past at whipping up the propaganda machine to encourage boycotting US imported goods or even travel to the US.

Still, it seems unlikely China would wish to engage in a full-scale financial war, by devaluing its currency and dumping US Treasury holdings, although some of the depreciation in the renminbi this summer was probably in anticipation of the tariffs.

There is also a limit to how much Beijing would wish to interfere with US companies operating in China, so as not to commit too much economic self-harm.

While the negative impact on China’s GDP from a tit-for-tat trade war is roughly double that of the US (as it is a smaller and more open economy than the US), it is growing at least twice as fast.

In addition, China probably has more policy tools available to offset the demand shock. In recent days this response is gaining traction with increasing tax rebates for exporters and a promised reduction in import tariffs on a wide range of goods later this year. Investors should keep a close eye on the reaction of the US Federal Reserve, which will clearly be key to the market outlook.

The central bank appears to be taking the view that it will respond once tariffs have been implemented but will not forecast an escalation.

From the central bank’s perspective, the trade war constitutes a negative supply shock – raising inflation, lowering growth – so it will be inclined to stick to its current guidance for interest-rate increases. But if the conflict triggers a significant tightening of financial conditions, this could derail the once-a-quarter hiking cycle we currently expect.

Overall, we are worried about the lack of moderate influences in the US administration and much hinges on China’s perception of US motives. It is unclear whether the White House hasa strategy – and if it does, what that strategy actually is.

Beijing, as a result, does not know whether the Trump administration’s objective is to reduce a trade imbalance, strike a deal to lower tariffs or merely to disrupt supply chains to reduce US reliance on China. If Mr Trump’s tactics are merely part negotiations, it should be possible to find a compromise that could even lead to improvements in the global trading system.

However, if the goal is more strategic and an attempt to curb China’s emergence as a global power, Beijing will take a tougher stance against any perception of bullying from the US.

For this reason and the rise in oil prices, we believe global growth risks are to the downside from the current decent momentum.

Tim Drayson is head of economics at Legal & General Investment Management