Corporate debt as a share of gross domestic product has risen dramatically over the past decade and, with it, leverage has increased and credit quality declined. Many investors are left wondering if credit markets could be the harbinger of the next economic downturn.

There are five key post-crisis changes to the most transparent sector of corporate debt – the public debt market – that investors should understand.

1. The corporate bond market is growing fast

The global debt market has changed dramatically over the past 12 years. In 2006, structured products accounted for 45 per cent of all issued debt.

After the global financial crisis, the fallout from the sub-prime mortgage market, a tighter regulatory framework and an increase in financial institution risk awareness led to a 50 per cent decline in the issuance of structural products.

Corporate bond issuance rose to fill the gap, leading to an evolution in the structure of debt markets, and, since 2009, corporate bonds have accounted for 57 per cent of all issuance.

The combination of low borrowing costs and yield-hungry investors (27 per cent of global government debt yields less than 0 per cent) has created the perfect environment for rises in both demand and supply.

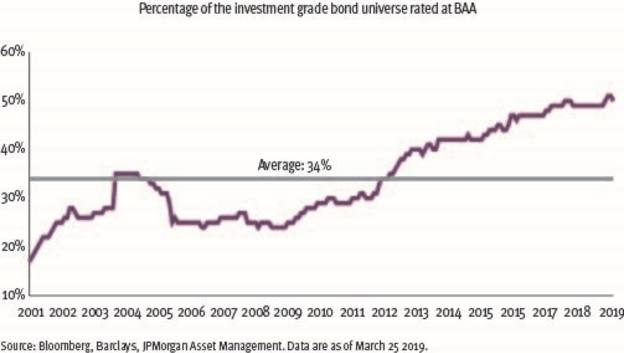

2. The quality of investment grade debt is in decline

Investment grade corporate bonds are like cuts of beef: at the top end, there is the tender filet mignon (AAA-rated bonds) and, at the bottom, the tougher rump steak (BAA-rated bonds).

When investors buy investment grade bonds, they may think they are getting the prime cuts but end up with the rump without being compensated for this.

With low borrowing costs and investors desperate for yield, companies rationally altered their capital structures or financing methods by issuing debt.

However, rising leverage and a potentially weaker credit position have created an overall decline in the quality of corporate bond indices.

Between December 2008 and January 2019, the share of the lowest-ranked bonds in global investment grade corporate bond indices has doubled from 24 per cent to 50 per cent.

The deterioration in index quality is a worrying trend, but there are mitigating factors when assessing the overall level of risk.

For example, many companies have used the easy funding environment to refinance existing debt at more favourable rates and extend their debt maturity profile.

As a result, if rates start to rise and financial conditions tighten, the pressure on funding costs will be felt only gradually.

Beyond this, credit is often thought of as a non-recessionary asset, in that it offers low levels of return and income so long as the economic outlook is benign.

3. Lenders have less protection

In 2018, an estimated 87 per cent of leveraged loan issuance was considered to have a lower-than-normal level of protection for bond holders.

These types of loans are known as ‘covenant lite’ where investors do not require borrowers to commit to maintain certain financial ratios.

Growth in this market has been driven by a higher level of private equity ownership, and the preference to raise capital with more favourable terms for the lender in the leverage loan market.

The default rate is running below the long-run average, but an untimely end to the credit cycle or an rise in market stress could drive defaults.

4. A debt wall is approaching

Between 2019 and 2022, $8.4tn (£6.42tn) of bonds will mature in global corporate debt markets, a record for this economic expansion. This is known as the “maturity wall”.

Investors are concerned for two reasons: first, large maturity walls are challenging when interest rates are rising as companies are forced to refinance debt at higher rates at the expense of profitability; and second, the interest coverage ratio – the number of times a company’s earnings can cover its interest expenses – has fallen from 8.6x in 2012 to 7.3x in 2018, close to the lowest level since 2009.

Together, these suggest that spreads could widen if companies face increasing pressure to service their debt.

The expansion-long hunt for yield has created demand for corporate bonds, helping to keep interest rates low. This should help ease the pressures of the approaching maturity wall.

Nonetheless, as maturing debt is rolled over, the focus should be on the quality of issuance and bonds that offer more protection for holders, even if that means sacrificing some additional yield.

5. Much of the debt has not been used for investment

In a perfect world, the money raised from issuing debt would be allocated to inward investment, including research and development and boosting productivity as a means to grow profits.

Over the course of this cycle, debt not used for refinancing has been put toward mergers and acquisitions activity, share buybacks and dividends.

In the US market, data on the use of bond proceeds is minimal, other than to specify whether or not funds are allocated to M&A activity. Since 2015, 29 per cent of non-financial US corporate debt issuance has been for M&A purposes.

In contrast, the data for leveraged loans and US high-yield bond issuers is more robust. Since 2010, 60 per cent of issuance has been dedicated to refinancing existing loans, with a further 27 per cent being dedicated to M&A activity.

Overall, only about 8 per cent of issuance has been focused on ‘general corporate’ activities, which includes business spending and investment.

Investment implications

As investors have been starved of income throughout this expansion, the corporate world has responded by issuing an increasing amount of debt of lower quality.

The structural changes to global debt markets may not present an immediate threat to portfolios. However, with renewed fears about the end of the credit cycle, the risks of what this may mean for markets is becoming prominent.

Part of having a resilient portfolio is understanding what you own and the risks.

Alex Dryden is global market strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management