Economic policy can never be completely divorced from politics.

Politicians – democratically elected or otherwise – determine fiscal, structural and trade policy. They also set the tone for monetary policy.

However, 2019 is proving just how volatile the results of this interaction can be for the economic and policy outlook.

In developed markets, support for large traditional parties has fractured, giving way to smaller parties that occupy the far right and left of the political spectrum.

These trends are testing norms on executive powers, representative democracy and central bank independence.

The recent European elections were a case in point. Further polarisation makes filling in the holes in Eurozone architecture even more challenging.

Meanwhile, the deeply polarised Brexit debate is monopolising policy space in the UK, with little end in sight.

Most importantly for global markets, the US political system is not working well.

The two major US political parties have further diverged ideologically in recent years, making fiscal cliffs a frequent concern.

Vast presidential powers are facilitating an erratic escalation of trade tensions between the US and China.

The administration is also putting pressure on the US Federal Reserve to act in accordance with US President Trump’s personal wishes.

Emerging and developed markets face quite different challenges. In the former, political institutions are often still developing, and are vulnerable to instability.

However, the past decade has proven that central bank independence is a stabilising force for countries that successfully separate politics and monetary policy. The US administration could learn a thing or two.

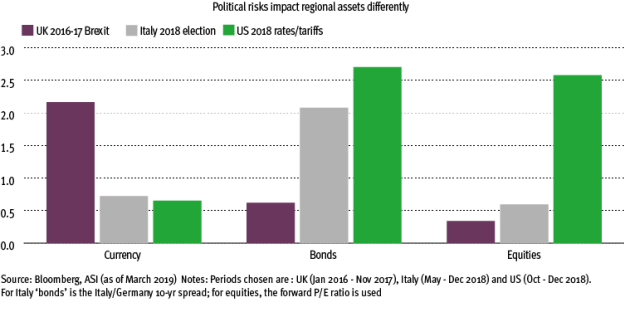

The impact of political uncertainty can differ significantly across asset classes depending on the region and specific form of political risk.

Analysing three recent periods of escalating uncertainty allows us to assess which asset classes were impacted most.

The three episodes are the fallout from the EU referendum in 2016; the aftermath of the Italian election that produced a populist coalition government; and the last quarter of 2018, when tight US monetary policy combined with international trade uncertainty. In the UK, the Brexit referendum impacted the currency most.

This reflected the need for the currency to adjust to the supply shock of leaving a free trade bloc, as well as sterling being a highly liquid asset with which investors can express risk appetite.

Gilts remained a relative safe-haven asset, while the FTSE 100 is highly internationally exposed so any derating from Brexit risk was partially offset by currency weakness.

This contrasts sharply with the Italian case, where the currency was not materially impacted in comparison with Italian bond yields (vs German) and the equity market.

The specific political risk is important: the populist Italian government created fears of fiscal profligacy and exit from the Eurozone.

In this context, the sell-off in Italian government bonds and in equities can be viewed as traditional risk-off investor behaviour, given both would be highly exposed to a dramatic loss of market confidence.

In the US, government bonds and the dollar are global reserve assets, so were relatively less affected by the market rout in late 2018.

Instead, trade and policy risk was more immediately priced into the highly liquid equity market. This reflected not only end-cycle fears, but also the fact that the market contains many companies exposed to US-China trade relations.

We have generally avoided directional sterling exposure, removed Italian bonds and been tactical with US equities.

As we said earlier, economic policy can never be completely divorced from politics.

Stephanie Kelly is senior political economist at Aberdeen Standard Investments