It is a common conception that investing in developed markets is a safer choice than emerging markets.

Emerging market countries have a reputation for higher political risk, lower economic stability and currencies that can be subject to dramatic swings.

However, the emerging asset class can display healthier, often attention-grabbing, economic growth when compared with the developed world.

EMs are exciting, dynamic and, in the hands of the right investment manager, have the potential to be hugely profitable.

Of the entire EM universe, one country that offers investors a truly long-term structural growth story in India.

Key Points

- India stands out among EM countries for its structural growth story.

- Demand for financial services in India is increasing as incomes climb.

- UK investors can use investment trusts to get exposure to Indian equities.

India is now the seventh largest economy in the world, with a nominal GDP of $2.5tn (£2tn).

Additionally, with the International Monetary Fund expecting growth in India to rise to 7.3 per cent in 2019 and 7.5 per cent in 2020, it is also the fastest-growing large economy globally.

Climbing the income ladder

From a consumer perspective, the country’s demographics also offer compelling reasons for long-term investment consideration.

While the Western world is suffering from an ageing population and declining workforce, India is seeing the reverse, with 50 per cent of its population under the age of 25.

An expanding workforce means rising household incomes and rapidly evolving spending habits, providing a boost to consumer spending in particular.

For instance, Indians traditionally bought shampoo in one rupee sachets (£0.01) as these were inexpensive.

As consumers climb up the income ladder, they begin to buy bottled shampoo and, latterly, a branded product.

This combination of a growing sales reach, combined with the sales of more profitable products, provides a strong investment case at an underlying stock level.

As another indication of this impressive growth, India’s per capita data usage is now three times higher than that of the other EM giant, China, as well as being the fastest-growing market for mobile phones globally.

Almost half of India’s internet users are between 15 and 24 years old and are online for up to 10 hours a day.

Since average incomes are growing fast off a low base, this generation will usher in the new wave of online consumption.

The enabling power of the internet creates new domestic consumer bases in emerging markets – boosting both local economic growth and the revenues of ‘connected’ companies.

EMs tend to offer investors a broader set of opportunities because many areas of the market remain underpenetrated.

India is no exception and investors will benefit from meaningful exposure to the country’s burgeoning financial sector.

Rising incomes are driving the demand for financial services across income brackets and since 2014 – when Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched his scheme aimed at improving financial inclusion for households – more than 300m families in India have opened bank accounts for the first time.

There remains the potential for retail banks to expand through better intermediation of savings (moving money from under the mattress and into the bank) and the cross-selling of financial products such as home loans, credit cards and insurance products.

So as in the shampoo example, increased reach combined with higher margin products should equate to a strong underlying investment opportunity.

But for all the potential rewards associated with investing in emerging economies, this asset class does carry risk.

Risk aware

One major factor that tends to deter investors from allocating capital to India is the perceived lack of corporate governance.

The area of the Indian quoted market that best represents the health and growth prospects of the local economy is the small and mid-cap sector, where many businesses are family-owned.

Historically, this type of business structure is synonymous with a lack of concern for minority shareholders.

In addition, investing further down the market cap curve increases risks as there is often less transparency, lower liquidity and, very often, a more fluctuating shareholder base, which can lead to big swings in share prices.

So mistakes are made, and the question then arises, what to do next?

Risk of this sort is best mitigated by owning a manager, with ‘feet on the street’ who has knowledge and understanding of the underlying company fundamentals.

That way, when mistakes occur, either because the company fails to meet investors’ expectations or an event unconnected to the company itself causes the share price to swing, the manager is well placed to make a call, either to exit and preserve capital or buy more in order to take advantage of the lower cost price.

However, in 2017, Mr Modi passed The Companies (Amendment) Act in order to help improve such corporate governance issues and the ease of doing business in India, while continuing to strengthen compliance and investor protection.

Indian business owners are increasingly aware of the importance of working alongside minority shareholders to propel growth and increase returns for all stakeholders.

Choose the right structure

For UK-based investors, tapping into single stocks in EMs can be a complex process, but investment trusts offer an easier way to gain exposure.

Investing in a closed-ended permanent capital structure can provide beneficial returns while mitigating some of the volatility and price shifts common to EM equities.

This type of vehicle can also take advantage of less liquid opportunities in small and mid-cap EM equities, an area that can generate high returns over the long term.

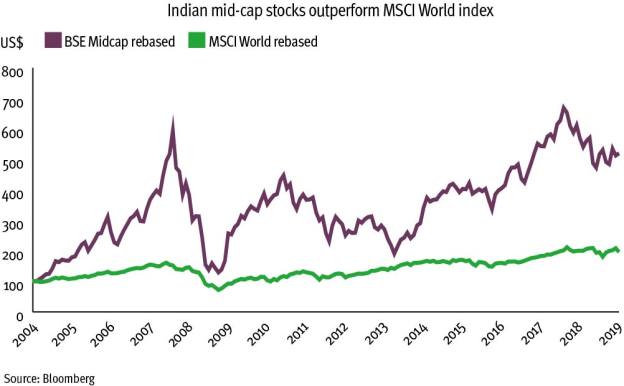

As illustrated in the chart, over the past 15 years, Indian mid-cap stocks have compounded at an impressive 13 per cent a year in US dollar terms, almost double that of the MSCI World index over the same period.

To truly take advantage of India’s growth, investors should get in early before valuations reach sky-high levels.

The key is to be selective, take a long-term approach and not be too concerned by pockets of underperformance.

David Cornell is manager of the India Capital Growth fund