Fee pressures, the difficulty of consistently outperforming markets and the very high-profile woes of the UK’s best-known stockpicker have not made life easy for advocates of active investing.

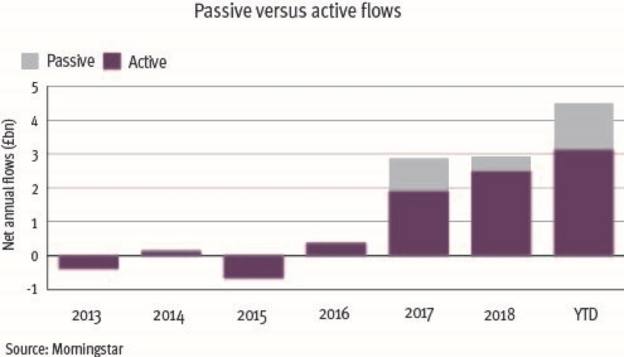

These factors, among others, have helped passives accrue a greater chunk of assets recently.

UK retail investors put £10.4bn into trackers on a net basis in the first eight months of 2019 according to Investment Association data, ahead of the £6.6bn net inflow registered by funds overall.

The growth of passive

Active still does have a place, particularly in those cases where managers can either consistently outperform the market or access a niche area that is difficult to track.

And values-based investments, from ethical approaches to funds paying attention to environmental, social and governance criteria, remain an area of growth for active managers because of the due diligence and careful selection involved.

Key Points

- Passive investing has become very popular in recent years

- Some companies are launching passive indices

- Investors need to be aware of their exposure

More than three-quarters of respondents to the Schroders 2018 Global Investor Study said sustainable investing, for example, had become more important to them in the past five years.

But ESG approaches and passive funds are not mutually exclusive. As Financial Conduct Authority chief executive Andrew Bailey noted in a 2018 speech to the IA’s culture conference, they should at the very least sit alongside each other.

“A longer-term shift towards passive investing goes alongside a desire for more ethical and socially responsible investing and a desire to encourage longer-term patient capital,” he said.

“Of course, these two developments can co-exist. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that they will, and that in doing so there will be some reclarification of the meaning of active investment.”

More notably, intermediaries who have a greater focus on ESG, or clients with an interest in this area, should pay attention to the fact that passive providers are increasingly entering the ESG space.

Morningstar recently noted that across Europe, active providers have been prolific in launching sustainable funds. Some 207 sustainable active funds launched in 2017, with 262 launches in 2018 and 142 in the first half of this year.

However, passive providers are also in on the act. Morningstar’s European Sustainable Funds Landscape note from the end of June found that 33 passive sustainable funds launched in 2017, with 43 new offerings coming to market in 2018 and 26 in the first six months of this year.

This has involved some big names, with S&P Dow Jones and MSCI each launching a range of ESG indices earlier this year. But a wider trend appears to be unfolding.

While the majority of launches may still be active names, the broad nature of passive investment means fewer trackers would be required to cover the market.

Passive sustainable funds are also attracting a “growing share” of net new money, according to Morningstar. Some 24.1 per cent of new inflows went into passives in the first half of 2019, compared with 24.3 per cent in 2018 and 20 per cent the year before.

As such, the product set available to investors is rapidly broadening out.

Values tilt

Where conventional passives invest across a market as it is, those with a values-based tilt tend to track an index that accounts for how a market’s constituents score on other criteria, such as how environmentally responsible they are.

“Conventional investment market indices like the S&P 500 or FTSE 100 tend to reflect a set of companies proportionally according to their market capitalisation,” explains Matthew Toms, of Heartwood Investment Management.

“Socially responsible investing indices go a step further, incorporating sustainable investment factors into their composition. This could mean only including those companies which score most highly on ESG issues.”

Like active ethical funds, index trackers with a specific tilt appear to have held up in performance terms versus their traditional counterparts.

Mr Toms notes that SRI indices have performed “very similarly” to their conventional counterparts over the longer term. And over the past 12 months some SRI indices, such as MSCI World SRI, have outperformed their unscreened counterparts.

All this means that investors with a preference for passive can follow the same approach when it comes to investing in line with their values. The usual dynamics apply: passives tend to be cheaper than active and, in many areas, can be difficult to beat in the longer term.

But as always, certain active managers will do well in the long term, and may be better placed to protect investors in a falling market.

Consider exposure

However, investors considering passive ESG funds, like those buying active, need to consider if the fund they are using gives them the exposure they want.

This can be tricky not just because investors can have very idiosyncratic views on ethical issues, but also because investment processes can vary hugely.

For example, active managers can choose whether to screen out companies that rate poorly on certain criteria, screen positively for those that do well on these metrics, carry out both exercises, or take an entirely different approach.

This, and the exact metrics managers use to assess potential investments can also vary.

This means that investors need to be aware of what exposure they are getting.

It also creates a risk of certain undesirable investments being inadvertently included in a portfolio if the screening approach is not robust enough.

When it comes to passive, this is also a potential risk.

Here, investors need to be aware of how tilted indices are constructed and exactly what criteria are being used to put them together.

In the listed equity space, a high level of transparency means due diligence on issues such as these should be possible.

But one active manager has argued that, for now, they retain an upper hand in the fixed income world.

Graeme Anderson, chairman of 24 Asset Management, said a lack of data meant it was a “major challenge” for fixed income indices to incorporate ESG.

“Typically ESG data is collected from publicly available report and accounts, which of course works well for quoted equity-based indices and investors,” he said.

“However, many bond issuers are unlisted, and as a result around one third of our funds’ holdings relate to issuers that are not represented in ESG databases, which requires us to carry out our own ESG research on these names.”

This is not to say passives are an inappropriate way to access all non-mainstream assets with an ESG approach.

But like other investors, those with an ESG bias should consider a variety of factors when setting the balance of active and passive fund holdings.

Dave Baxter is deputy personal finance editor of Investors Chronicle