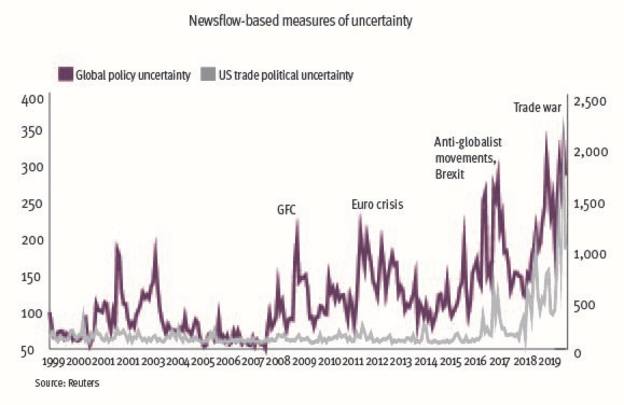

The main culprit was elevated uncertainty, which has become the defining feature of politics and monetary policy and has undermined decision-making in the real economy.

In the year ahead, we do not see any meaningful resolution to the trade and geopolitical tensions that have defined 2019.

Key Points

- There has been no resolution to the trade and geopolitical tensions of 2019

- Unpredictable policy is holding back investment decisions

- There is not expected to be a technical recession

As a result, growth next year is likely to be lower than we had previously expected, and to stay lower for longer.

What are the implications for investors?

This combination of slowing global growth and persistent geopolitical uncertainty will create a fragile backdrop for markets in 2020 and beyond.

Our short-term outlook for global equity markets is cautious, with the risk of a downturn in shares and other higher-risk assets more elevated than in a more ‘normal’ market environment.

Longer term, investors may need to get used to market returns that are likely to be lower than in previous decades.

A lower growth equilibrium?

The shift in the policy climate has long been coming.

The backlash against free trade and open markets has been building since the global financial crisis and it exploded into life with the EU referendum in June 2016 and the US election of Donald Trump less than five months later.

But in 2019, policy uncertainty wrong-footed central bankers and markets alike by weighing heavily on economic activity, particularly in the industrial sector.

So much so that within months, expectations for gradual central bank tightening morphed into interest rate cuts in the US and fresh quantitative easing in the euro area.

The growth slowdown was made worse by the trade tensions between the US and China and the Brexit negotiations.

Our analysis shows that unpredictable policy is holding back economic activity more than ever.

It is unusual to see the kind of synchronised global industrial slowdown that we are seeing at the moment – and it is mainly trade-led.

The good news is that we do not expect a technical recession – two straight quarters of contraction – in the US nor anywhere else in world.

A big reason for this is the fact that the industrial sector represents only a small share of overall economic activity.

On average, we estimate that every 1 percentage point change in manufacturing output has a 25 basis-point impact on the much larger services sector.

Still, the not-so-good news is that we expect global economic growth and interest rates to be lower for longer.

The way policy uncertainty weighs on the real economy is like a tax, insofar as it effectively causes companies and households to discount the future more heavily.

Right now, there seems to be a perception out there among businesses and households that the rules of the game have changed – that we are leaving behind an era characterised by international co-operation and stable trading arrangements and entering a new, more uncertain one.

This hinders long-term planning and hampers economic activity.

If the lost investment is not clawed back, the supply-side potential of the economy will be permanently lower.

In addition, reduced trade and lower foreign direct investment could mean any potential productivity gains are less likely to be exploited.

So as this process of deglobalisation unfolds, we are forecasting growth of around 1 per cent in 2020 for both the euro area and US economies, and 1.2 per cent in the UK.

In China, we expect growth to slow below 6 per cent for the first time in almost 30 years.

Subdued returns

Investors have experienced spectacular returns over the past few decades because of two of the strongest equity bull markets in history in addition to a secular decline in interest rates from 1980s highs.

The future looks somewhat less rosy.

Over the medium term, we expect that central banks will eventually resume the normalisation of monetary policy, leading to more attractive valuations for financial assets and a higher return outlook compared to our current forecasts.

Nonetheless, the return outlook is still likely to remain much lower than the experience of previous decades and, in particular, of the post-crisis years.

Looking ahead to the next 10 years, we expect annualised UK equity returns to be much more subdued than in the past, at around 4 per cent to 6 per cent.

The return outlook for non-UK equity markets, from a UK investor’s perspective, is expected to be in the 3.5 per cent to 5.5 per cent range, which is very similar to that of UK equities.

Nevertheless, exposure to other global equity markets in a broadly diversified portfolio can help to manage financial market volatility and avoid excessive concentration in just one market.

Our projected outlook for annualised UK and non-UK fixed income returns for the next decade is around 0.5 per cent to 1.5 per cent.

While this may look low, we still expect high-quality bonds to play a key role in reducing risks and improving stability within a portfolio.

Faced with this lower-return environment, investors may be tempted to look at strategies that overweight assets with higher than expected returns, or higher yields.

However, these strategies are unlikely, by themselves, to escape the low-return environment.

As our prior research has shown, investors will have a better chance of investment success if they focus on factors that are within their control, such as saving more, increasing their investment horizon, spending less and controlling investment costs.

Peter Westaway is chief economist and head of investment strategy for Vanguard Asset Management, Europe