At the same time, government debt from countries including the UK and US has seen yields fall to new record lows just above (and in some cases below) 0 per cent as investors hunt for safe havens.

There is no denying these are extraordinary times, with a virus now infecting the globe at a time when economic growth was already fragile.

Central banks have responded with tried-and-tested methods, with the Federal Reserve pushing through an emergency 50 basis points rate cut at the start of March and US politicians signing off a $2tn economic relief package at the end of the same month.

The Bank of England has followed suit, slashing the base rate to a record low of 0.1 per cent. Arguably, these moves have exacerbated — rather than dampened — volatility, causing investors to take flight from risk assets.

The only real king among asset classes in this panic moment has been cash, with investors rushing to buy short-dated treasuries and selling everything else.

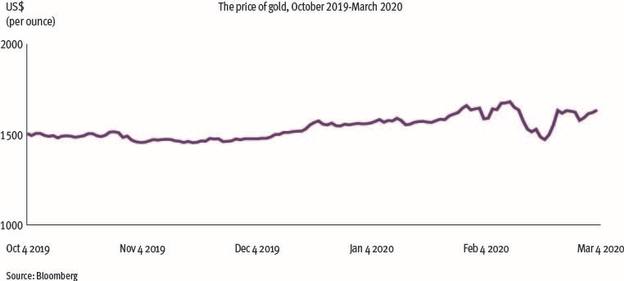

A traditional safe haven that is yet to act as such in a meaningful way is gold.

The precious metal has, like other asset classes, seen heightened volatility during the crisis, enduring some swings lower and some sharp rallies (particularly the week beginning April 6), but over the medium term this lack of overall gains could serve it well.

While the outlook from here is dependent on the path coronavirus takes over the next few months, there are a number of tailwinds for gold that could see it break through the $2,000 mark this year.

Key Points

- Yields on typical risk-off assets are likely to prove unsustainable

- Gold is a possible safe haven

- The gold price is a long way off its recent high of $1,837 during the Eurozone crisis

Low rates

Firstly, there is the situation with real rates, which have never been lower.

With yields turning negative on UK debt, already deep in negative territory in Europe and Japan, and paying just a few basis points in the US, an ever-growing chunk of the world’s debt supply is now in negative territory.

At these levels, investors are holding bonds for safety, totally disregarding the fundamentals of investing in the hunt for protection at any cost.

But they will be forced to search beyond bonds to preserve their wealth over the long term because, as it stands, all investors are doing by buying bonds at these levels is locking in a guaranteed loss when inflation is accounted for.

Indeed, unless investors expect there to be no growth for the next 10 years, agreeing to lend to governments at such levels could come back to haunt them in the long term.

That is because the situation in fixed income is simply not sustainable, and we have already seen moves out of bonds after they dipped to record lows, with yields climbing in recent days.

When investors therefore come to reassess and look for alternatives, gold could be a standout option.

Gold is underowned by investors globally, with gold demand down 1 per cent in 2019 as a huge rise in investment flows into exchange traded funds and similar products was matched by the price-driven slump in consumer demand, according to the World Gold Council.

It means that gold accounts for around 10 per cent of portfolios globally today, down from peaks above 70 per cent back in the 1950s.

Given the headwinds facing the global economy from the coronavirus — and the added complication of an oil price shock — we can only see this increasing.

Supply stalls

Gold mining production stagnated in 2019, halting a decade-long trend of increasing supply.

While it will take time to filter through to prices, stagnant supply levels at a time of panic in traditional assets could act as a tailwind for the price if demand continues to climb.

One issue that has also acted as a temporary headwind is margin requirements, which were raised by brokers amid the volatility in markets.

This means backers of gold have had to hand over additional capital to ensure they can continue trading, and many have not been minded to do so.

When this is resolved it will provide another tailwind for the price, especially when combined with falling supply.

Somewhat counter-intuitively, the gold price ended the month down in February and has been volatile in March, despite being set against an overall global economic landscape characterised by lacklustre economic growth, falling inflation, and high levels of debt.

Much of this has been due to large funds forced to deleverage.

But this story has further to run.

Markets are at a mature stage of the credit cycle, and the disruptions and dislocations of the coronavirus may prove to be a catalyst for the trade-war slowdown to tip into a global recession.

The last time we had such an event was 2011 when confidence was wobbling around the world and the Eurozone was on the brink of splitting apart amid the Greek crisis.

The response from investors then was to buy gold, with the price hitting its highest ever level of $1,837 (£1,462).

This time around we are still some way off that mark, but the crisis we are experiencing is unfortunately still very much at the beginning.

Monetary and fiscal stimulus will likely result in currency debasement and increase gold’s allure relative to the fiat currencies subject to money printing.

As such, if investors are looking for somewhere to invest amid the volatility, they should strongly consider an allocation to gold given where real rates of interest are, the measures central banks are taking, and the uncertain nature of the virus itself.

Clark Fenton is manager of the RWC Diversified Returns fund