It would be understandable to assume this is Covid-19's fault, but we can’t really blame the pandemic for any of 2020’s casualties so far.

Fraud is the root of the recent insolvency at Wirecard – rated Baa3 just 6 days before default – courtesy of some Filipino bank statements fabricated long before any of us had heard of Covid-19.

Structural challenges and terrible timing have also pushed UK shopping mall operator Intu into administration.

Investment grade defaults are rare (most years there are none) and can be incredibly difficult to identify in advance.

A key feature of any investment grade bond default is that - by definition - its issuer probably looked fine a year ago.

To fall from grace so quickly requires some combination of mismanagement, fraud, an act of God and spectacularly bad luck.

Pandemic impact

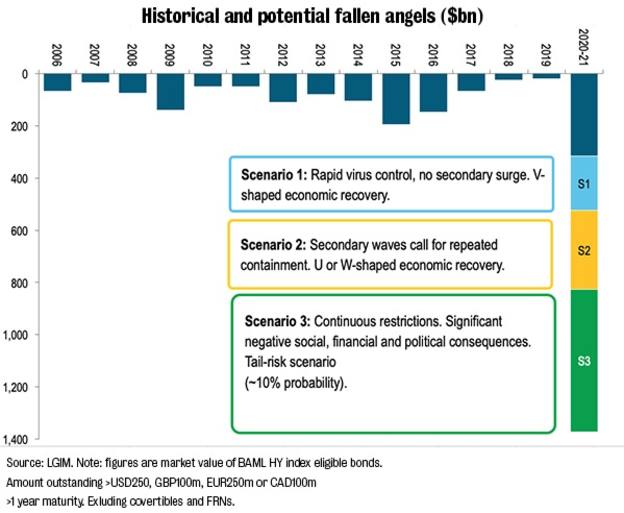

Covid-19 ticks a number of these boxes, and although the pandemic has not yet led to any investment grade defaults, it has already pushed a record $300bn of bonds to junk this year.

We think there is worse to come, and even in a best case, V-shaped economic recovery scenario, we expect fallen angels to nearly double over the course of this crisis.

This could grow to $800bn under a U or W shaped recovery, and to $1.4trn under a very worst case (currently low probability) great depression scenario.

Unsurprisingly we expect this crisis to push up defaults, but – perhaps counter-intuitively – we think that for investment grade companies this rise may take a long time to transpire, and that the peak may be lower than in previous crises.

So despite our terrifying fallen angel predictions, this crisis may not be the disaster for investment grade bond investors that it appears.

Defaults risk

Very simply, when companies default it’s usually because they have run out of cash.

For firms that were investment grade when the pandemic hit, this looks unlikely to happen any time soon because central banks around the world have provided all the liquidity that they need.

Even companies without direct access to these schemes have benefited from the resulting bond market frenzy and funding from the high yield market.

For the most vulnerable companies, such as the airlines, liquidity alone is not enough.

Here we see parallels with the global financial crisis, in that some large firms will be considered worthy of bail-outs, albeit for different reasons.

A number of companies may be allowed to fail, but when we try to imagine the 'Lehman' of this crisis, we are looking at a relatively small pool of candidates.

Heading into the global financial crisis almost one third of investment grade corporate bonds were issued by the banking sector, while today’s equivalent - Travel and Leisure - is just 1 per cent of the market.

Importantly, markets and credit rating agencies have had several months to digest the impact of the pandemic, and the wave of downgrades to high yield means that the investment grade index looks safer than it did a few months ago.

The cruise liners are long gone, as are many of the airlines.

We wouldn’t go so far as to say that credit ratings have now caught up with the economic outlook, as we’re still expecting many more downgrades.

Investor opportunities

But we think that the vast majority of investment grade companies are well positioned to survive, and as active managers we have the ability to skew portfolios away from those firms that might not be so lucky.

For an investor buying credit today, the headline increase in default rates this year may sound alarming, but it is actually fairly irrelevant – it’s safe to assume that Intu and Wirecard would be absent from any actively managed portfolio constructed today.

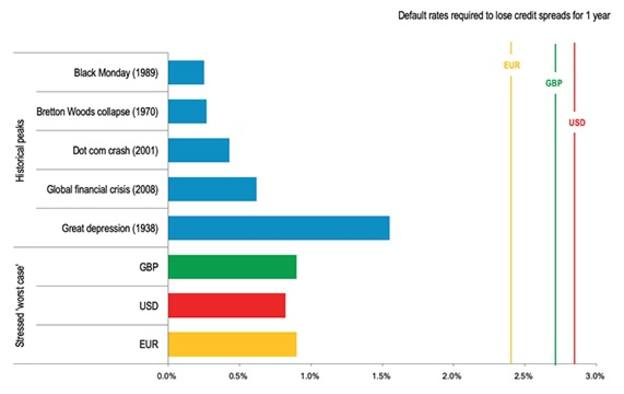

Instead we should consider current investment grade credit spreads versus the potential peak default rate through this crisis.

Across currencies, spreads are tighter than at their March peak, but they remain wide by historical standards.

In EUR, GBP and USD annual default rates of over 3% would be required to erase the carry offered by current credit spreads.

Based on history it’s reasonably absurd to think we could hit that figure during this crisis: in the great depression they peaked at around half this level.

Even if we assume that all of our expected fallen angels happen within 12 months, and apply great depression default rates at these lower ratings, we can only engineer a peak default rate in the mid 2s - still comfortably below the level required to offset the benefit of current spread levels.

Historical peaks and current worst case scenario default rates

As investors weigh second wave infection fears against the wall of central bank support, it’s reasonable to expect continued volatility throughout the summer.

But we think that investment grade bondholders can cross defaults off their list of worries, at least for now.

Madeleine King is co-head of Pan European Investment Grade Research, Active Fixed Income at Legal and General Investment Management