It has been suggested that the Treasury wants to generate £20bn from increased tax revenue, but this amount pales into insignificance when estimates put the present cost of Covid-19 at around £300bn.

It is also arguable whether the Autumn Budget is the right time to introduce tax increases — after all, we are still in the middle of a global pandemic.

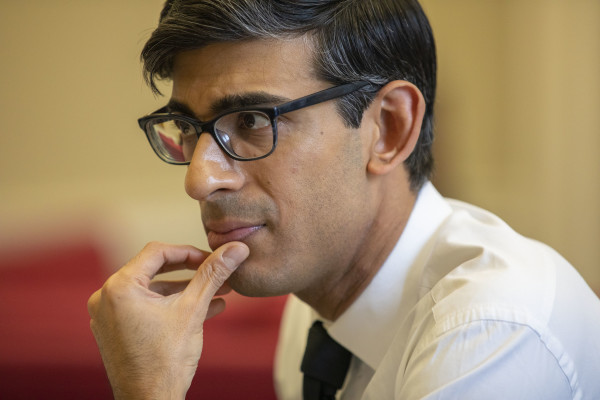

With the economy so fragile and jobs on the line, UK chancellor Rishi Sunak and the government need to be very mindful about drastic changes.

It remains an incredibly uncertain time, as we enter the crucial winter trading period and businesses will be looking over their shoulder as the furlough scheme comes to an end.

The government also needs to consider the international outlook with Brexit firmly on the horizon, and Mr Sunak needs to be mindful of inward investment from a corporate and private wealth perspective.

It is inevitable that the government will need to increase taxes in the future, and this is my run down on which areas of the UK tax system could be under review.

Capital gains tax

There has been speculation for some time — even prior to the pandemic — that CGT rates would increase.

The headline rate of CGT of 20 per cent is considered to be very favourable, and there are growing calls that it should be increased to 28 per cent across the board or possibly aligned to income tax rates (up to 45 per cent).

The threat of an increase to CGT was compounded further by Mr Sunak asking the Office of Tax Simplification to offer its proposals on simplifying the tax.

The latest statistics from HM Revenue & Customs show that the Treasury generated £9.5bn in 2018–19. This was a record year for CGT receipts, but represented only 1.5 per cent of the total tax take. Any rate increase is unlikely to make a significant impact on overall tax revenue.

Key Points

- The government has to raise money to pay for Covid-19 relief

- Income tax is a likely target for tax rises

- Capital gains tax in main residence is on balance not likely

It is also worth noting that there has already been a CGT increase this year when Mr Sunak, in his first Budget as chancellor, cut the entrepreneurs’ relief lifetime limit from £10m to £1m, costing an affected taxpayer £900,000 in CGT.

There is a compelling argument that CGT should be abolished completely as part of the wider reform of capital taxes and the fact it raises so little in overall tax revenue. However, this is highly unlikely from a political standpoint.

Politically, it is a very easy move for the government to raise CGT and sends the right message that the wealthy — who pay CGT — are taking on a higher tax burden.

Inheritance tax

Over the past 10 years the government has been trying to look at ways to raise more tax revenue from IHT.

Critics have long argued that IHT is an optional tax and can easily be avoided by someone if they plan to give away or spend their wealth before their death.

Previous chancellors have tinkered with IHT rules to close certain planning opportunities, but revenue from IHT remains broadly flat.

Reform of IHT is long overdue and it requires careful consultation, alongside reviewing capital taxes more generally. It is unlikely dramatic reform will be announced in the Autumn Budget, but changes could happen in the future.

Like CGT, IHT raises very little in tax take for the Treasury, so it is questionable as to how much impact any changes would have on revenue generation.

One of the key areas of the present IHT system under risk is the ‘seven-year rule’ for gifts — known as the potentially exempt transfer rule for gifts — and this could be abolished and replaced with a lifetime gift allowance.

It is unlikely that the 40 per cent rate of IHT would be increased, as this is one of the highest rates in the developed world, but it could be feasibly reduced to 20 per cent if a lifetime gift allowance is introduced.

Income tax

If the government could do anything at the Autumn Budget, a universal increase to income tax would be at the top of the list. An increase in the basic rate of income tax to 21 per cent would raise £4.7bn.

The government would probably want to pursue the reintroduction of the 50 per cent income tax rate for those earning more than £150,000; however, the historic evidence suggests that the 50 per cent income tax rate — which applied from 2010–13 — did not actually lead to an increase in tax revenue.

Any income tax increase could be made temporary, with the additional revenue being directed to the NHS.

It is very easy for the government to increase income tax and is likely to be accepted by most, mainly on the grounds of sentiment given the widespread impact of the pandemic.

An increase to income tax would go against the government’s ‘triple-lock’ and could therefore be met with strong political criticism.

As the government keeps reminding everyone, these are unprecedented times and the rule book could be cast aside.

National insurance

When Mr Sunak announced the Self-Employment Income Support Scheme in April, it came with a warning that the self-employed would need to pay for the bailout through future tax rises.

Over the past five years, there have been more signals that the tax regime for the self-employed worker should be put on an identical footing to the employed worker.

This could mean that Class 4 NIC would be increased from 9 per cent to 12 per cent — on profits up to £50,000 — and the small tax benefit of being self-employed would be completely removed.

In addition, the government could introduce further changes to how personal service companies, or contractor companies, are taxed, and this could include aligning the dividend tax rates with the main rates of income tax.

The self-employed community has been aggrieved at the lack of government support during the pandemic and focused tax rises will not be well received, but it seems inevitable that changes will happen soon.

Pensions

Pensions tax relief is estimated to cost the government £25bn and restricting the relief should go some way to meeting the Treasury’s revenue target of £20bn.

The highest earners are now limited to only £4,000 of tax-relievable pension contributions and they may not feel overly concerned if this relief was capped to the basic rate.

It would also simplify the pensions regime, which has caused serious confusion for those with defined benefit pension schemes, including consultants working in the NHS.

Main residence relief

Main residence relief is one of the most generous reliefs in the UK’s tax system, allowing homeowners to make tax-free capital gains when they sell their main home.

With numerous changes to the taxation of residential property over the past 10 years, it is one of the last remaining ‘tax grabs’ on residential property for the government and could generate significant revenue in CGT.

The government should be nervous about introducing any tax changes that impact the housing market.

It would also seem counter-intuitive to introduce a change that restricts movement in the housing market when the stamp duty land tax holiday announced by the chancellor in July was designed to do the opposite.

Nimesh Shah is chief executive of Blick Rothenberg