Article 2 / 4

Guide to Responsible InvestingBaby boomers are interested in responsible investing too

If you had to associate a particular demographic with responsible investing, you may instinctively think of millennials. But earlier generations are also considering values alongside potential returns.

Cleona Lira, a chartered financial planner at Celtic Financial Planning, who counts ethical investments among her areas of specialism, says she has a “great number” of older clients who are “very interested” in sustainable investing.

And climate is the biggest factor on the minds of both younger and older clients, says Lira.

Jeannie Boyle, executive director and chartered financial planner at EQ Investors, likewise sees an interest in sustainable investing among those who are “definitely not millennials”.

“I work with a number of typical retiree clients, all the way up into their 80s, who care very passionately about the impact that their investments have on the world. I’ve worked with people in their 60s who have very high thresholds for including certain companies in a sustainable portfolio.

“There’s always degrees to which people want to influence their portfolio and set out ideas or thresholds for inclusion, but caring about climate change and making sure investments are sustainable from that perspective is common across the generations.”

So why might we typically associate younger generations with responsible investing?

Louis Williams, head of psychology and behavioural insights at Dynamic Planner, refers to the concept of psychological distance.

“It’s similar if we think about views on climate change. The more we might distance ourselves from the benefits of a company managing their risks, the less we might act.

“So that might be a reason why it’s suggested that older generations may not want to act, because they feel that the benefits of them doing this are actually for future generations, and not necessarily for their own.”

Williams also says that any generational differences may be due to greater choice in ESG-related investments today.

“Those differences may be because there is more available now, when that younger generation is starting to invest. There’s more funds that have those ESG factors already being taken into consideration, [compared to] 50 years ago or so when the older generations may have started to invest.”

An activist vs pragmatist approach

Clémence Chatelin, head of sustainable investments at Paradigm Norton, says millennials can be more proactive in asking about responsible investing.

But she adds: “We’ve just started talking to the bulk of our clients about it, and depending on what their views are, generally they’re very open as well.

“I tend to find that with more senior clients, they would probably ask a lot more of the questions about returns first, before making their decision.”

Implementation is another potential difference between generations, Chatelin says.

“When you get to clients who are more wealthy, and that tends to be older clients, then you look at investments that have tax advantages, such as enterprise investment schemes.”

Lee Coates, co-founder of compliance consultancy ESG Accord, also describes a potential activist versus pragmatist approach between generations.

“Younger investors are probably more likely to be more restrictive in the things they don’t want. When you’re younger, you have a more activist mentality, but as you get older, you become more pragmatic. So a younger activist may wish to go for an ethical fund that won’t invest in certain things.”

Meanwhile a pragmatic older investor might opt for a responsible fund, says Coates, giving the example of a fossil fuel company making the energy transition to cleaner alternatives.

“Both parties can be classed as sustainable investors,” he adds.

Responsible investment horizons

Tim Fassam, director of government relations and policy at Pimfa, says that time horizons are the most likely difference when advising different generations on responsible investing.

But Fassam adds this may not always be the case, citing the possibility of a retiree looking to pass wealth down to the next generation with a horizon of up to 40 years, and a younger person looking to invest to buy a property with a horizon of up to 10 years.

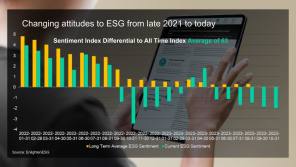

Ben Sears, head of UK solutions at Pacific Asset Management, which co-developed profiling tool EnlightenESG, also highlights how investors’ sustainability preferences can evolve over time, particularly with younger clients with potentially longer investment horizons.

“Because you have such a long time, you can see how a client’s sustainable preferences have evolved. Perhaps the client has started very ‘light green’ by dipping a toe in, and has moved over time towards being very sustainable, or perhaps the other way.”

For clients with a longer investment horizon, Fassam highlights the role that ESG can play in future-proofing investments.

“If you believe what governments are saying about net zero, and you have a younger person who’s looking to invest over their career and for retirement, they might be looking to invest over 30 or 40 years. That long term investment will absolutely have to take into account environmental concerns, because the companies that will succeed, to a certain extent, will be the ones that understand what a net zero reality means.

“Over the longer term, there’s likely to be very little distinction between return and sustainability, because sustainable firms will be the ones that succeed.

“If you’re not considering climate change when thinking about what the most appropriate long-term investments are, you are likely to be missing one of the key drivers of the global economy over the coming decades.”

Chloe Cheung is a features writer at FTAdviser