With ever-increasing awareness and emphasis on environmental, social and governance factors, particularly among the next generation, should trustees be taking a positive ESG stance on their investment policies?

Historically, ESG investment has been thought to compromise performance, and although there are studies purporting to show the opposite, research earlier this year from index provider Scientific Beta suggested ESG investment still has a way to go.

But why should that matter? 'I am a trustee, and I have been given the responsibility for managing the trust fund. I will do it my way', you might say.

Unfortunately it is not that simple.

All trustees, whatever the creator of the trust might direct, have a fiduciary duty.

That is a duty to act at all times in the best interest of all their beneficiaries. And that duty overrides any personal views, values or agenda. So trustees will be judged by an objective standard.

Trustee duty

One might argue: 'We as trustees are holding money for current and future generations, shouldn’t we be investing in a way that creates a better world for them? That seems to be more what our beneficiaries care about'.

Leaving aside the need to balance the expectations and needs of future beneficiaries with those of the current beneficiaries, trustees run the risk of challenge from beneficiaries if the investments underperform. And at the moment there is no legal protection against that.

The point has arisen in the context of charities.

The Charity Commission guidance makes clear that charities can follow ESG criteria if – back to the fiduciary duty – it is in the best interests of the charity as a whole.

For example it would clearly be counterproductive to invest in a way that is likely to deter donations.

But it is clear that stewardship of a permanent endowment is not given that latitude, save in extreme examples – an alcohol addiction charity might be excused for avoiding drinks companies.

Charities are more complicated than private family trusts, since one can usually identify with a fair degree of accuracy who the beneficiaries of a family trust are, and if necessary size up the likelihood of them causing you a problem, or indeed their strength of feeling on ESG issues.

Assessing value

But is it really the place of trustees to decide to prioritise the greater good over financial return when investing other people’s money – in effect, deciding for the beneficiaries what is important to them?

And to do that without knowing how important the financial support from the trust for those beneficiaries might turn out to be?

The question becomes: at what point will ESG become so embedded as to be of no impact one way or the other on the price of investments?

There are of course two elements to the price of a share: one is the value of the trade and the other the desirability of the company (think Facebook).

It must surely follow that companies that score badly on ESG will be less desirable in a world that values ESG highly, and that desirability element of the share price will reduce, negatively impacting the value to the investor. That in turn will encourage companies to up their game on ESG, until that becomes the norm.

But until investors start voting with their feet, will that happen?

It might be that it would require legislation obliging companies to do more on ESG, or perhaps tax on those bits that are quantifiable; carbon emissions, for example, or individual investors making decisions to reduce the exposure to such companies.

Does that not include trustees? Remembering the fiduciary responsibility, I think the answer is no.

In the mainstream

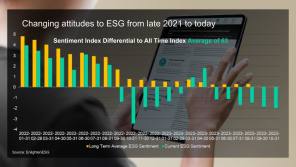

What does seem to be happening is that socially responsible investment is itself already becoming more mainstream.

And as more companies take their ESG responsibilities more seriously, the risks and historic underperformance associated with ESG investing are starting to disappear.

Clearly this is good news for those wishing to pursue an ESG investment policy, not least trustees, who may soon find that the decision as to whether to make ESG responsible investments becomes the same as sound and sustainable investment in a pre-ESG-aware world. So, for example, doing good for the world does good for the investment portfolio.

Until then, trustees will have to wait and see whether this increasingly asked question is going to be tackled at a legislation level.

We await greater clarity on the Charity Commission guidance for charity trustees, and it has been argued that there should be a change to the Trustee Act 2000 – the main piece of legislation that governs the running of trusts – which would help family trustees.

There is one other possibility for trustees.

There is a rule that says that if all the beneficiaries of a trust have capacity – that is to say they are over 18 and of sound mind – then collectively they can bring the trust to an end dividing the trust fund between them.

Given they have that power, they could collectively instruct the trustees to adopt an ESG investment policy. Although if I were a trustee I would want an indemnity from them, lest they change their minds.

Jeremy Curtis is a partner in the private wealth team at law firm Cripps Pemberton Greenish