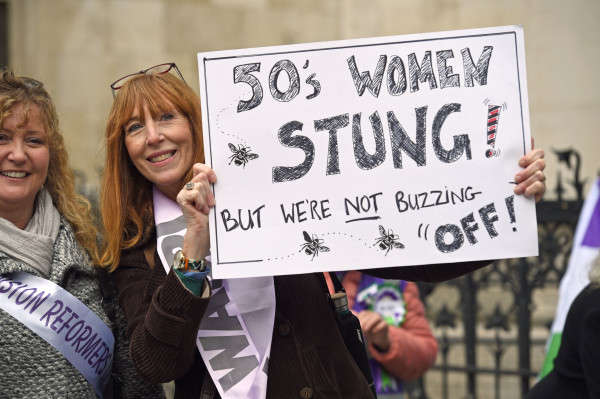

The decision by the High Court to dismiss the women’s state pension age challenge has not dulled the fervour of those campaigning for compensation

The case has also shone a bright light on the pensions gender gap and the actions that women should be taking to protect themselves in retirement.

On October 3 the High Court rejected claims brought by members of campaign group BackTo60 that the increase in the state pension age affecting women born in the 1950s was discriminatory. Lawyers for the claimants said raising the state pension age discriminated against women born after 1950 on the grounds of their age, and also put women “at a particular disadvantage to men”.

Michael Mansfield QC added that the claimants and many other women born in the 1950s were not told about the changes until shortly before their expected state pension age at 60, causing “significant detriments” to many of them.

Key points

- The High Court rejected claims that the increase in the state pension age for women born in the 1950s was discriminatory

- The PHSO is looking into the question of maladministration

- Women need to plan for further potential changes to the state pension age

At the heart of the matter are changes that were made to the Pensions Act in 2011, which is reported to have affected 3.8m people. The government passed legislation in 1995 (part of the Pensions Act) to equalise the state pension age for men and women at 65. That meant that the state pension age would rise for women by five years.

In 2011 under changes to the act, women’s state pension age increased more quickly to 65 between April 2016 and November 2018. From December 2018, the state pension age for both men and women started to increase to reach 66 by October 2020.

In the 1995 act, any woman born between April 6 1954 and May 5 1954 was set to receive their pension on May 6 2018.

Under the changes, a woman born in the same period will have to wait an extra 18 months until November 6 2019 to receive her pension.

Since 2010 various campaign groups have emerged calling for the changes to be overturned. According to the campaigners, some of those worst affected have felt suicidal, while others have become homeless or have had to sell their properties to survive.

False premises

BackTo60 accuses the government of deferring the state pension of women born in the 1950 under the false premise of equality and longevity.

The group says: “As a result, thousands of women across the UK have had their retirement plans annihilated. Their mental and physical well being has been very negatively affected. Likewise, their family relationships have deteriorated so much so, that many have expressed the loss of their identities and self-esteem diminished.”

BackTo60 is calling for full restitution of pensions going back to the age of 60 for women affected. Joanne Welch, campaign director at BackTo60, says: “1950s women mainly stayed at home, had part-time jobs, looked after children, the elderly. Their income was supplemented by the main breadwinner –the man.”

“Let’s say at 58, a woman born in 1953 receives a letter to say your pension is going to be 18 months late, what could you do at that age to change your financial planning?”

Women Against State Pension Inequality is calling for fair transitional arrangements for all the women affected.

Angela Madden, finance director and chair of Waspi, says: “We are campaigning for some sort of compensation payment to recognise the distress and loss caused to all these women.

“We don’t expect it to be for £160 a week that the pension is now, but we would like a good percentage of that to tide us over, because we expected our pension at 60.”

Backto60 has launched a crowdfund to appeal the High Court’s rejection of its case, while Waspi has lodged its complaint with the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman.

Baroness Ros Altmann, a former pensions minister, says: “I have always feared that a discrimination case would be very hard to win in this situation. The policy change was supposed to be about gender parity.”

While the judicial review was under way, the PHSO had to take a pause in looking into Waspi’s complaint, but with court proceedings finished for now, it is back on the ombudsman’s table.

The PHSO has the power to decide whether the Department for Work and Pensions is guilty of maladministration and, if so, to recommend redress.

So far Prime Minister Boris Johnson has pledged to look into the case, while DWP secretary Thérèse Coffey is set to meet with Conservative MP Tim Loughton and Labour MP Carolyn Harris, co-chairs of the All-Party Parliamentary Group on State Pension Inequality for Women, in “due course”.

Speed of change

Helen Morrissey, pensions specialist at Royal London, says: “It is absolutely right the state pension age is equalised, but these changes have happened very quickly.

“It is hard not to have sympathy for these women. The Waspi women were massively disadvantaged because women coming into the workforce now are being auto-enrolled into a pension. With the cohort of women born in the 1950s, a lot were not encouraged to save into a pension and some were not allowed to.

“For us as providers it is making sure we get the message out about preparing well in advance for retirement.”

Tom Selby, senior analyst at AJ Bell, says: “Given that the country is careering headlong into a general election and the opposition parties have pledged as yet unspecified help for the women affected, lobbying the Conservative Party that is pursuing an increasingly populist agenda could prove effective.

“While the fight continues in practical terms, those who face an income shortfall have limited options. Some will continue to work longer, while there has also been a spike in the number claiming out-of-work benefits. Others may have been in the luckier position of having other sources of income to live off while they wait to receive their state pension.”

Ms Morrissey adds: “If women are able to continue in their jobs, that’s great. For other women they should try and get some guidance to see if there are any benefits they could claim to try and bridge them over. Or are there any savings they can use?”

But Mr Selby warns that younger women should take heed and protect themselves against any further possible changes to the state pension by the government. He says: “Both men and women need to understand that the state pension is a benefit rather than a guaranteed right.

“As a result, it is possible a future government will reduce the amount you are entitled to or adjust the age at which you will receive it. In short, you can’t rely on the state pension.

“It is therefore sensible to make your own plans and save as much as you can, as early as you can, taking advantage of the bonus available through tax relief, matched contributions from your employer, and compound growth over time.”

Baroness Altmann adds: “You can’t rely on receiving state pensions at a particular age and you need to plan for private pensions or other income to have the best chance of the lifestyle you want or need when older.

“I think provision should be made for both men and women to have early access to some state pension on health grounds or if they are caring for others and cannot work.”

She suggests other actions the government could undertake include lowering the age for qualifying for pension credit.

Ima Jackson-Obot is deputy features editor of Financial Adviser and FTAdviser