Auto-enrolment has had a significant effect on pension saving behaviour with more women now in a workplace pension, than ever before, although more work needs to be done to close the gap between women and men.

In a briefing note on understanding the gender pension gap, published today (May 11), the Institute for Fiscal Studies said auto-enrolment has substantially increased pension participation among employees with women now only slightly less likely to be in a pension at all ages than men.

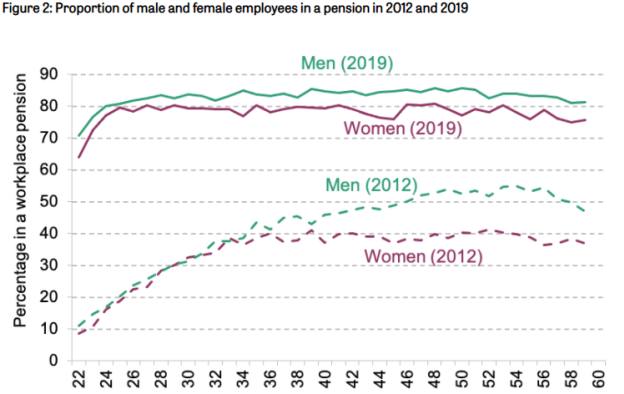

The IFS found, before auto-enrolment was introduced in 2012, the proportion of men and women saving into private pension was similar until around age 30, but it then branched off with men increasingly likely to be saving in a pension as they got older whereas women tended to plateau.

But the pattern in 2019 was different and rather than participation changing at a particular age, women were only slightly less likely than men to be in a pension at all ages, and the level of participation among both genders was considerably higher.

The IFS said this highlighted the importance of examining gender differences in saving rates, rather than just accrued pension wealth or pension income.

It said focusing on the latter could lead to policies which aim to fix problems which have already changed over time.

The IFS stated: “It is important to understand more about the drivers of previous and current differences in pension saving rates between men and women, in order both to understand the wider consequences of automatic enrolment and to provide insight into what actions, if any, are warranted to address any continuing gender pension gap.”

Laurence O’Brien, a research economist at IFS and one of the authors of the report, said: "Prior to automatic enrolment a big gender pension participation gap opened up from the early thirties onwards. This pattern has been hugely changed by automatic enrolment though it remains the case that men are more likely to be a member of a workplace pension than women.

“More needs to be done to understand the drivers of these differences and therefore the wider consequences of automatic enrolment, and what action, if any, might be needed to address the gender pension gap going forwards."

According to the IFS, there are three main drivers of a difference in pension income between men and women.

The first is a difference in the length of working lives, the second is different savings rates with the two genders tending to make varying contributions, and the last is a difference in investment strategies with men and women choosing different risk levels.

In a report yesterday (May 10), the IFS called on the government to nudge people to save more into their pensions later in their working life, particularly when their children leave home, mortgages are paid off or student loans come to an end.

IFS modelling suggested an average graduate with a student loan debt and two children should increase their pension contributions from around 5 per cent of pay before the children leave home to between 15 and 25 per cent of pay after that.

That would mean making two thirds of their pension contributions after the age of 45.

amy.austin@ft.com

What do you think about the issues raised by this story? Email us on FTAletters@ft.com to let us know