Last Friday morning was relatively calm, the UK gilt market was ready for a "mini" Budget that was to contain an energy price announcement and some tax changes, which were likely to result in additional supply of government debt.

The promise to households to help them through a tough winter would need to be funded via the issuance of gilts, and 10-year yields had risen from 3.1 per cent to around 3.5 per cent through the week leading up to Friday morning.

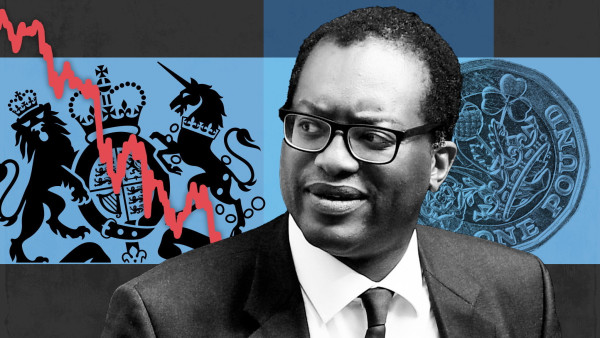

The "mini" Budget would be one for growth, and the chancellor indicated it would lead to a 2.5 per cent trend rate of real GDP growth over the medium. There were more tax cuts than had been anticipated, which surprised the economics profession and the market, the details of which are well documented elsewhere.

The Debt Management Office was expected to issue around £130bn of government bonds this fiscal year. Following the "mini" Budget, gross issuance is now expected to be closer to £190bn and in the following fiscal year, it could be closer to £220bn.

Remember that the price to the government/taxpayer of the energy price cap is open-ended and the ultimate cost of this policy will be dependent on the price of gas in the wholesale markets, this year and next.

That seems significant, even if it stood by itself – and it does not. Aside from the question of whether these measures will indeed create 2.5 per cent real GDP growth over the medium term, the fundamentals do not present an overwhelming attractive proposition for investors buying these new gilts – 25 per cent of the gilt market is held in foreign hands.

Unfunded cuts to government revenue; substantial additional supply into a market that has already had a very challenging year; the Bank of England being due to commence selling gilts back into the market; and, of course, very high levels of inflation were all set against a backdrop of a forecast imminent recession.

These are just some of the reasons why the gilt market fell on Friday following the Treasury’s announcement – the 10-year yield marched higher closing the day at 4.1 per cent.

Over the weekend market participants digested the news while the chancellor seemed to double down on the bet, suggesting in interviews further tax cuts would come in due course. Consequently, the selling pressure continued at 8am on Monday and through Tuesday, with yields on the 10-year gilt reaching 4.5 per cent.

Bond prices are more sensitive to changes in yields if they have a longer maturity. The longest nominal UK bond matures in 2073 and the trading price for this bond fell more than 30 per cent between Friday morning and Wednesday morning.

The inflation-linked equivalent also maturing in 2073 has more sensitivity to yield changes due its longer duration and the price of this instrument fell 62 per cent over the same period as yields surged.

It is hard to overstate exactly how extreme these moves are. The excess volatility and sheer speed with which these yields rose, in what should be a relatively stable market, caused the BoE to step in on Wednesday.

The pension industry was suffering, and a mismatch between assets and liability opened up quickly, raising margin calls that prompted further gilt sales to fund margins, exacerbating the situation.

The BoE released the break, pausing the quantitative tightening programme, and simultaneously slammed the accelerator and initiated a new unsterilised quantitative easing programme.

The immediate effect of this action was a rally unlike anything seen in a developed world government bond market. The 2073 nominal gilt rallied 41 per cent from its lows into the close, the 2073 inflation-linked gilt more than doubled in price terms.

Yes, you are right in what you are probably thinking now: QE should, all things being equal, add to inflation, it is stimulative. Adding to the UK’s inflation problem in the same week the BoE was due to tighten monetary conditions extends both the government and the BoE’s troubles.

Why is the central bank turning 180 degrees and seemingly making the inflation problem worse? To stop the UK government bond market from imploding.

Now there appears to be relative calm in the debt markets again, attention turns to the currency. Sterling is weak and has sold off aggressively since Friday.

A model used by the BoE suggests that for every 10 per cent depreciation in the currency (on a trade-weighted basis) UK inflation could increase by around 1.5 per cent at the headline level.

Conflicting policies are now at the heart of the problems facing the government and the central bank.

How should investors navigate this market? In my mind, an allocation to very short-term nominal gilts makes a great deal of sense, and avoiding credit spread in what is likely to be a recessionary environment. Yields have risen in anticipation of more rate hikes from the BoE, designed to suppress inflation expectations.

This does present investors with an income stream that gives the asset class its name back. The short-end recommendation means that the bonds will mature in the near future and allow the investor to roll the cash proceeds into another short-term gilt and potentially benefit from an even higher yield.

The other asset class that deserves a place in a portfolio is longer-dated inflation-linked gilts. Given the recent turmoil, these gilts now offer investors true protection from inflation; real yields – that is, the yield available after the effects of inflation – are positive for the first time in a decade.

Align a financial liability or a retirement date with the bonds’ maturity and investors can preserve their capital in real terms, which means the asset class can be particularly useful in financial planning.

Thomas Wells is a fixed income fund manager at Sanlam Investments