A string of recent data highlighting poor performance records for active fixed income funds has turned the spotlight away from underperforming active equity funds.

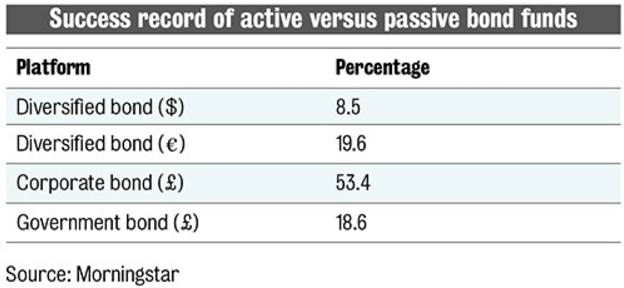

In February, Morningstar’s European Active/Passive Barometer found that, over the past decade, fewer than a quarter of fixed income funds had managed to both outlive and outsmart their average passive peer in nine out of 12 categories.

S&P’s Persistence Scores, published in July, which measure how many active bond funds available in the US market have maintained a high performance, found that none of the 14 government long bond funds that achieved top quartile performance in 2015 were in the top quartile in 2019.

Key Points

- Active fixed income funds have been underperforming their passive peers.

- Government bond funds and fees could be skewing performance.

- The ability of bond fund managers to navigate geopolitical uncertainty might help them standout from passive products.

Furthermore, none of the top quartile 26 global income funds in 2015 held that position in 2019.

At the end of July, US research company Dalbar calculated mutual bond funds had underperformed inflation over one, 10 and 30 years.

Robin Powell, a journalist and a campaigner against active fund managers, whose LinkedIn account provides daily accounts of the success of passive investing while skewering the activities of the likes of Neil Woodford, cites all of those reports.

He quotes from the Morningstar report by stating: “Active management, the researchers concluded, is typically ‘priced to fail’.”

Higher fees

While it does not look great, all is not bad. S&P’s research shows that its overall figures are skewed somewhat by the woeful performance of government bond funds, as corporate bond and high-yield funds have a much higher chance of beating passive.

This probably has something to do with the historically low returns for government bonds over the past decade, which have given a greater weighting to fees in investor outcomes.

S&P evidences how the fee bargaining position of institutional investors gives them a much better chance when investing in active than in passive.

Naturally, if you speak to an active manager, you will hear a lot more positives.

Research by smart beta AQR from 2018 shows active delegated managers consistently outperform in the arena of fixed income – which suggests that higher fees plays a key part in underperformance for retail funds.

However, another paper from AQR – The Illusion of Fixed Income Alpha – provides a caveat for this by stating that many active funds simply outperform the index by increasing exposure to riskier parts of the market, such as high yield and emerging markets.

Pimco is also keen to point out why the dynamics of active bond funds differ from those of active equities and are not “priced to fail” in the same way.

Jamil Baz, head of client solutions and analytics at Pimco, says that the proportion of the equities market held by passive investors is, by logic, a mirror image of all the holdings of active managers. So, with the fee differential between the two, active equity investors are bound to underperform as a whole.

However, fixed income markets have three key players: active and passive managers; non-economic investors such as central banks or pension funds; and insurance funds, which hold bonds for reason of liability matching rather than outperformance.

As this third group is not seeking to maximise returns in the same way an active manager will, so says Pimco, there is a transfer of alpha from constrained players to mutual funds.

Mr Baz further adds that the type of absolute return strategies in which Pimco specialises depend very little on the direction of the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate index; it relies on off-benchmark positions, mean reversion, currency trading and the use of derivatives.

This can lose or win you money, but it is likely to be a very different beast from a passive fixed income fund in your asset allocation.

Active v passive

This message of being as different from passive as possible is echoed by Royal London Asset Management.

Jonathan Platt, head of fixed income at RLAM, says: “Too many managers run ‘me to’ strategies that are not capable of producing excess returns after fees. This is a problem of both pricing and mindset.

“Basically, an approach of trawling through the same universe of commoditised credit bonds and expecting clients to pay for active management and superior performance won’t wash in the long term.”

Even the proponents of passive management agree on this point.

Ed Gibson, head of financial services at Oxford and London-based financial planners Shaw Gibbs, usually favours passive investing for his clients, but uses active funds for niche, less efficient markets or for reasons of diversification.

“Under normal circumstances, we might be 100 per cent passive in fixed interest,” he says. “But, because of the level of [geopolitical] uncertainty now, we are looking to hedge our bets.”

Calculating how geopolitical events could impact government bonds – which make up 57 per cent of the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate index – is something that active fixed income managers specialise in, so this makes sense.

Robo-adviser Nutmeg also largely uses passive funds for their cheapness and their transparency of holdings, which allows the company greater precision in its asset allocation.

Nutmeg duly relies entirely on passive exchange-traded funds issued by iShares, Lyxor and UBS for much of its assets under management, with the glaring exception of a Pimco short-dated bond ETF.

Shaun Port, chief investment officer at Nutmeg, explains that the Pimco Pan-European Credit fund is a proxy for cash, but with better long-term returns.

He says: “It’s an ultra-short credit portfolio that is effectively a money market fund and has a yield better than cash. It has good long-term outperformance and it gives us a diversification away from UK credit.”

David Rowley is a freelance journalist