PARTNER CONTENT by ARTEMIS

This content was paid for and produced by ARTEMIS

Jack Holmes is co-manager of Artemis Funds (Lux) – Global High Yield Bond

FOR PROFESSIONAL AND/OR QUALIFIED INVESTORS ONLY. NOT FOR USE WITH OR BY PRIVATE INVESTORS. CAPITAL AT RISK. All financial investments involve taking risk which means investors may not get back the amount initially invested.

Reference to specific stocks should not be taken as advice or a recommendation to invest in them.

The high-yield market could do with a good PR agency. Barely a day goes by that we don’t have someone decrying the irrational behaviour of investors within the asset class. When yields are particularly high, commentators opine that investors are allocating money to companies on immediate verge of bankruptcy; when yields are low, the view is that investors are falling over themselves to give money to barely credible business models. As someone involved in the market, I could be forgiven for wondering if I had made a career mistake.

But once the immediate despair has passed and rational thought takes over, the arguments made by the critics do not stand up. The first point – and one that has been oft repeated over the last six months or so – is that the high-yield market will crash as interest rates rise. According to the narrative, the low interest rates since the global financial crisis have driven investors to lend money at barely positive interest rates to 'zombie' companies that will fail and leave investors nursing heavy losses.

But there are a lot of holes in this argument. First, are interest rates really so low? While high-yield credit spreads are far from the widest seen at times of stress, they are more or less at the median level observed over the almost quarter of a century for which we have data. If we exclude periods of extreme market stress (the financial crisis, the energy bust, and the Covid-19 lockdowns) then current spread levels are above the median levels seen in the past.

In terms of absolute yields, US-dollar-denominated BBs and Bs (which together make up 65% of the developed global high-yield market) trade at 5.49% and 6.81% respectively[1]. The median level of fundamental credit losses for these ratings categories going back to 1983 has been 0.3% and 2.0% respectively. This implies a very healthy buffer over likely credit losses of almost 5% for both of these core parts of the market. While there are undoubtedly areas of concern – emerging-market high-yield and CCC-rated securities being the most obvious – the core of the high-yield market is offering attractive yields relative to the fundamental credit risks being taken.

Duration risk or credit risk?

But, the argument continues, rising interest rates will cause high yield – as the riskiest part of the fixed-income market – to underperform. Well, the simple fact is that ‘risk’ is not a linear concept within fixed income. Crudely, there are actually two opposing forms of risk – duration (exposure to interest rates and yield changes) and credit (risk of the entity you’re lending to going bankrupt) risk.

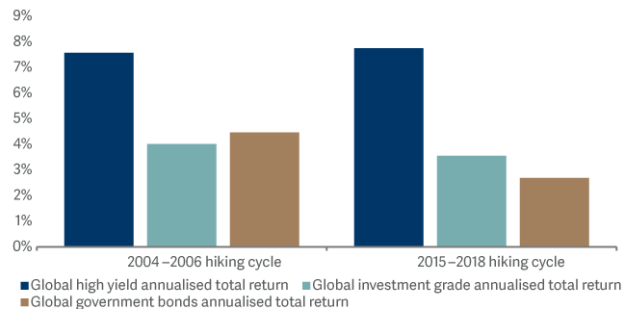

High yield has a lot of credit risk – hence the higher yields to compensate – but actually very little duration risk. And yet duration is the part of fixed income that tends to get hurt in central bank hiking cycles. So while government and investment-grade bonds (which tend to have a lot of duration risk, and not so much credit risk) suffer in hiking cycles as yields rise, high yield actually tends to perform well. Indeed, over the last two Fed hiking cycles high yield has significantly outperformed wider fixed income and delivered high-single-digit percentage annualised returns (see Chart 1).

High yield outperforms in hiking cycles

Improving quality in the high-yield market

And the argument then goes on, surely all this loose monetary policy over the last decade has meant that lots of companies have received loans that shouldn’t have? I would counter this by saying that over the last 20 years – and particularly over the period since the global financial crisis – the high-yield market has got better and better in terms of credit quality. Put simply, the high-yield market has never seen a higher proportion of lower-risk (BB-rated) credits than today; or a lower proportion of higher-risk (CCC-rated) credits.

This has happened for a variety of reasons – downgrades of very good companies from investment grade have helped, as have private equity sponsors learning from their mistakes in the lead-up to the global financial crisis, and the cleansing effect of both the 2015/2016 and Covid default cycles. However, the sum of these factors is that – unlike other parts of the credit market, such as leveraged loans – high yield has never been higher quality than it is today.

High yield or equities?

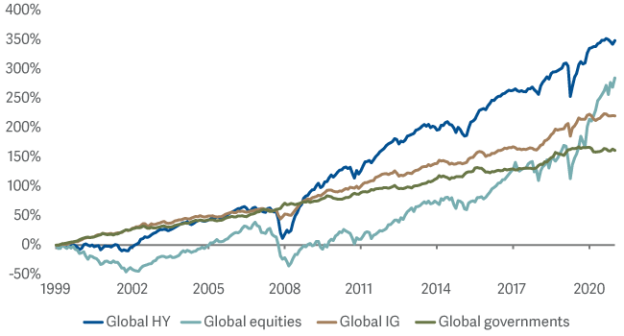

The critic then accepts that high yield is usually a beneficiary of the hiking cycle and could do well as we move from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening. But the next point raised is whether investing in equities would give more solid long-term returns with less exposure to heavy losses around recessions. In fact, high yield has produced higher total returns than equities over the past 20 years (see Chart 2).

20 years of outperformance...

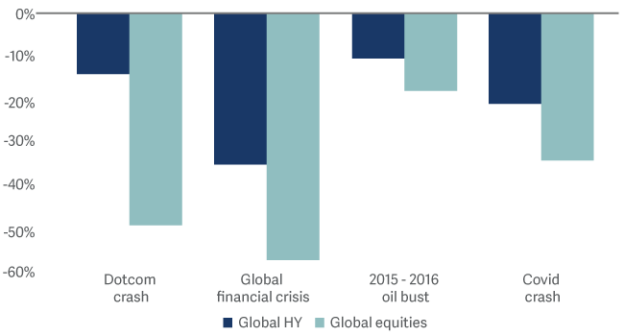

In addition, it is better insulated in sell-offs. As Chart 3 shows, peak-to-trough high yield has outperformed equities in every major sell-off since the millennium.

Lower peak-to-trough drawdowns than equities

To conclude, apart from the strong performance through hiking cycles, vastly improved credit quality, superior long-term returns against equities, and improved drawdown (and recovery) characteristics, what has high yield ever done for us?

Jack Holmes is co-manager of Artemis Funds (Lux) – Global High Yield Bond, for more information please visit the fund page.

[1] Source BoAML 26 April 2022.

Reference to specific stocks should not be taken as advice or a recommendation to invest in them.

FOR PROFESSIONAL AND/OR QUALIFIED INVESTORS ONLY. NOT FOR USE WITH OR BY PRIVATE INVESTORS. This is a marketing communication. Refer to the fund prospectus and KIID/KID before making any final investment decisions. CAPITAL AT RISK. All financial investments involve taking risk which means investors may not get back the amount initially invested. High Yield bond investments are usually associated with higher investment risk – particularly the risk of default by the company issuing the bonds

Investment in a fund concerns the acquisition of units/shares in the fund and not in the underlying assets of the fund.

Reference to specific shares or companies should not be taken as advice or a recommendation to invest in them.

For information on sustainability-related aspects of a fund, visit www.artemisfunds.com.

The fund is a sub-fund of Artemis Funds (Lux). For further information, visit www.artemisfunds.com/sicav.

Third parties (including FTSE and Morningstar) whose data may be included in this document do not accept any liability for errors or omissions. For information, visit www.artemisfunds.com/third-party-data.

Any research and analysis in this communication has been obtained by Artemis for its own use. Although this communication is based on sources of information that Artemis believes to be reliable, no guarantee is given as to its accuracy or completeness.

Any forward-looking statements are based on Artemis’ current expectations and projections and are subject to change without notice.

Issued by: Artemis Investment Management LLP which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority; in Germany, AI Management (Europe) GmbH; in Switzerland, Artemis Investment Services (Switzerland) GmbH.

Find out more